過去幾年,各大專欄介紹了許許多多的經(jīng)濟趨勢,,但極少能夠像“情緒衰退”(vibecession)那樣引起廣泛關注,。該詞由凱拉·斯坎倫于2022年7月提出,指那種“盡管傳統(tǒng)經(jīng)濟健康指標表現(xiàn)良好,,但人們仍然對經(jīng)濟感到‘不爽’”的現(xiàn)象,。眾多數(shù)字媒體都對這一話題進行過探討,包括最近又有許多文章報道稱,,隨著近幾個月消費者情緒的反彈,,2023年來勢洶洶的情緒衰退在2024年已經(jīng)歸于平淡。

但這場情緒衰退的始作俑者是誰呢,?簡而言之,,還是男人的問題。

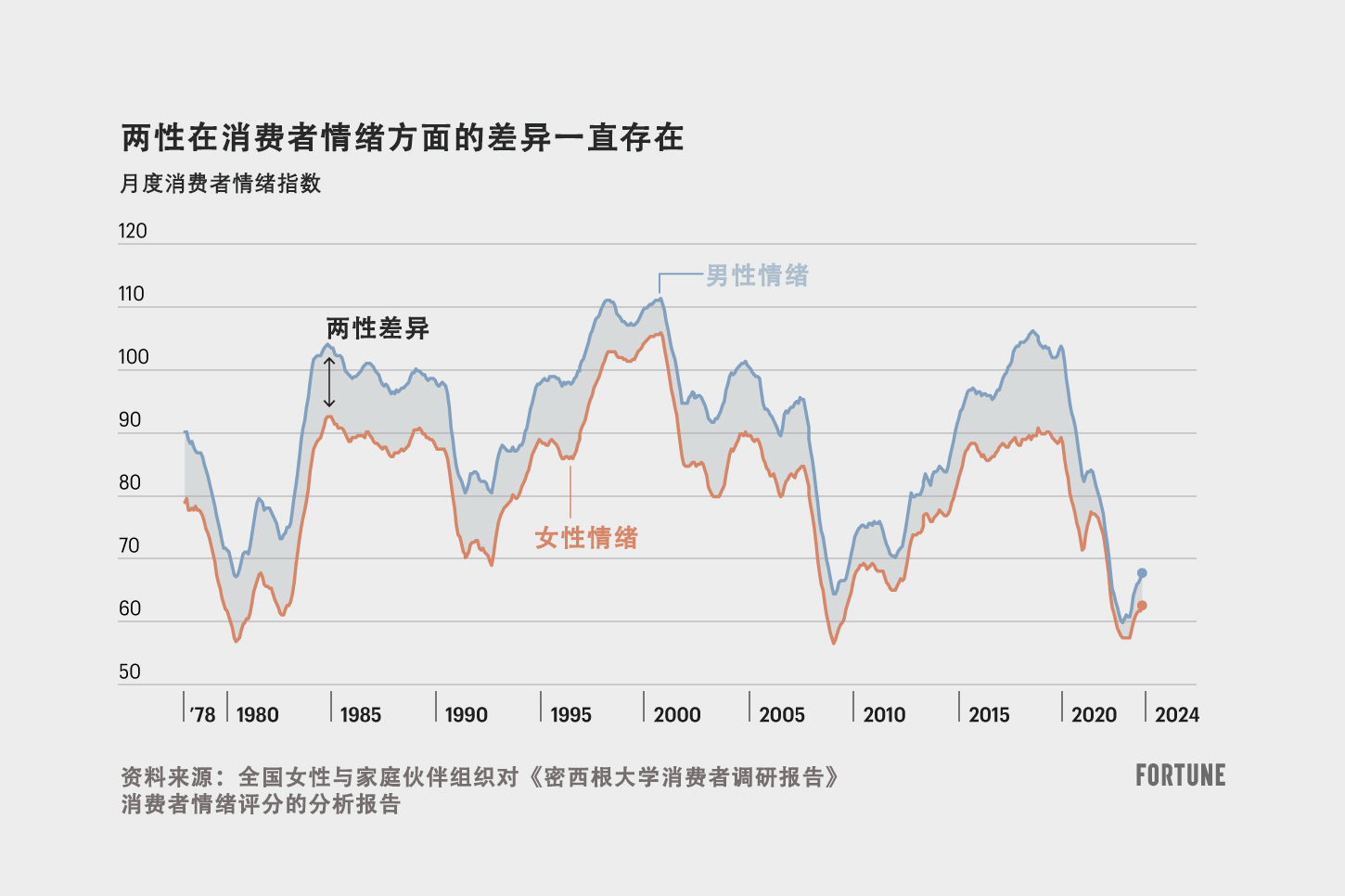

在看待經(jīng)濟問題時,,男性通常比女性更為樂觀,。我們通過研究發(fā)現(xiàn),在密歇根大學(University of Michigan)過去46年所做的月度消費者調查中,,僅有15個月男性比女性對經(jīng)濟更悲觀,。新冠疫情爆發(fā)以來,消費者情緒全面下滑,,然而我們通過分析發(fā)現(xiàn),,在有關情緒衰退的討論中,還有一個值得注意但尚未得到討論的問題,,那就是兩性在經(jīng)濟感受方面的差異顯著縮小,。情緒衰退不僅意味著所有人都對經(jīng)濟感到悲觀,,更意味著男性終于有了和女性相同的感受。

經(jīng)濟依舊在按照男性喜好的方式運行

看完本段內容,,你就會很容易理解為什么女性一直對經(jīng)濟持悲觀態(tài)度,。直到密歇根大學調查開始前不久的1974年,女性才獲得了開設銀行賬戶或申請信貸或貸款的權利,,經(jīng)濟自主權才得到了保障,。甚至在20世紀后半葉,女性還經(jīng)常身處不平等且充滿敵意的工作環(huán)境,。美國最高法院直到1986年才將性騷擾認定為職場性別歧視行為,,此時千禧一代中年紀較長的已經(jīng)出生。女性還要兼顧工作和家庭,,而唯一一部明確致力于幫助女性平衡上述需求的全國性法律《家庭和醫(yī)療休假法》(Family and Medical Leave Act)頒布距今僅三十年。

在這些法律和政策進步的幫助下,,女性得以更好地參與到經(jīng)濟活動中來,,也可以更好地享受經(jīng)濟發(fā)展的成果(這種變化自然也體現(xiàn)在了消費者情緒的變化上)。20世紀80年代,,女性的消費者情緒比男性低12.5%,。到2000年代,這一數(shù)字縮減到了10.2%,。過去兩年,,這一數(shù)字一直保持在5.7%的水平。但事實是,,經(jīng)濟仍舊在按照男性喜好的方式運行,。正因如此,雖然女性創(chuàng)辦了近一半的初創(chuàng)企業(yè),,但女性持有的企業(yè)卻只拿到了不到2%的風投資本,。正因如此,在有數(shù)十億資金流入主要由男性創(chuàng)辦的各種人工智能初創(chuàng)企業(yè)的時候,,育兒勞動力規(guī)模較新冠期間卻幾無改觀,。正因如此,女性工資依然僅為男性的78%(有色人種女性的差距更大),。

現(xiàn)在已經(jīng)到了2024年,。我們有了機器人吸塵器,手機看一眼就能夠解鎖,,還有了太空游客,。但我們生活的社會仍然要求女性在全職工作的同時,還要全職照顧孩子和年邁的父母,,而對女性的支持卻微乎其微,。兩性的消費者情緒差異也可以反映這種“魚與熊掌不可兼得”的困境,。

如果我們不是只在男性對經(jīng)濟與女性一樣悲觀時才關注消費者情緒問題,而是把重點放在提升女性情緒的政策上,,就會怎樣呢,?例如,在2021年年初,,由于女性消費者情緒的提升幅度顯著高于男性,,在“情緒衰退”期間,兩性在消費者情緒方面的差距明顯縮小,。女性消費者情緒為什么會出現(xiàn)這種變化呢,?很可能是因為《美國救援計劃法案》(American Rescue Plan Act)得到了通過。該法案提高了兒童稅收抵免,、兒童保育救援資金標準,,還加強了其他一系列重要的家庭支持項目,這些舉措極大鼓舞了在新冠疫情第一年被迫在照顧家人與有償工作之間做出痛苦選擇的女性,,增強了她們對未來經(jīng)濟穩(wěn)定的信心,。雖然我們不敢說一定是因為這個原因,但鑒于這些計劃的受歡迎程度,,尤其是在女性中的受歡迎程度,,包括我們在內,許多人都認為這種解釋站得住腳,。

在2022年的“情緒衰退”時期,,男性和女性的消費者情緒基本為同步變化,整體消費者情緒在2022年6月跌至谷底,,也是在這個月,,通脹水平達到歷史最高,男性消費者情緒則跌至歷史最低,。2023年,,兩性情緒差異再次擴大。那么2023年發(fā)生了什么呢,?新冠疫情初期匆忙搭建起來的社會安全網(wǎng)宣告解體,,工作場所日益恢復“正常”(而女性在這種“正常狀態(tài)”中一直處于弱勢地位),。盡管我們無法按照種族或殘疾狀況對情緒進行分析,,但其他分析的經(jīng)驗表明,有色人種女性和殘疾女性要想在這樣一個自己受到排斥的體制和國家生存,,必須付出極大的努力,。

筆者想要強調的是,在我們思考和討論經(jīng)濟問題時,,亟需將重點轉向消費者情緒,。但隨著兩性消費者情緒差異的再次出現(xiàn),,相關討論再次遭到我們忽視,這種情況令人擔憂,。雖然許多優(yōu)秀記者已經(jīng)寫過媽媽們在尋找托兒所時所遇到的困難,,也介紹過她們在平衡工作與家庭責任時所承受的精神負擔,但這些討論卻很少成為核心經(jīng)濟話題,。

女性占總人口的一半以上,,占總勞動力的將近一半,還是消費支出重要推手,,但她們對經(jīng)濟的感受卻從未得到足夠重視,。這種情況必須改變。(財富中文網(wǎng))

安維沙·馬朱米德(Anwesha Majumder),,衛(wèi)生科學碩士,,是美國全國女性與家庭伙伴組織(National Partnership for Women & Families)的經(jīng)濟學家。凱瑟琳·加拉格爾·羅賓斯(Katherine Gallagher Robbins),,博士,,是全國女性與家庭伙伴組織的高級研究員。

Fortune.com上發(fā)表的評論文章中表達的觀點,,僅代表作者本人的觀點,不代表《財富》雜志的觀點和立場,。

譯者:梁宇

審校:夏林

自1978年以來,,兩性消費者情緒變化情況。

過去幾年,,各大專欄介紹了許許多多的經(jīng)濟趨勢,,但極少能夠像“情緒衰退”(vibecession)那樣引起廣泛關注。該詞由凱拉·斯坎倫于2022年7月提出,,指那種“盡管傳統(tǒng)經(jīng)濟健康指標表現(xiàn)良好,,但人們仍然對經(jīng)濟感到‘不爽’”的現(xiàn)象。眾多數(shù)字媒體都對這一話題進行過探討,,包括最近又有許多文章報道稱,,隨著近幾個月消費者情緒的反彈,2023年來勢洶洶的情緒衰退在2024年已經(jīng)歸于平淡,。

但這場情緒衰退的始作俑者是誰呢,?簡而言之,還是男人的問題,。

在看待經(jīng)濟問題時,,男性通常比女性更為樂觀。我們通過研究發(fā)現(xiàn),,在密歇根大學(University of Michigan)過去46年所做的月度消費者調查中,,僅有15個月男性比女性對經(jīng)濟更悲觀,。新冠疫情爆發(fā)以來,消費者情緒全面下滑,,然而我們通過分析發(fā)現(xiàn),,在有關情緒衰退的討論中,還有一個值得注意但尚未得到討論的問題,,那就是兩性在經(jīng)濟感受方面的差異顯著縮小,。情緒衰退不僅意味著所有人都對經(jīng)濟感到悲觀,更意味著男性終于有了和女性相同的感受,。

經(jīng)濟依舊在按照男性喜好的方式運行

看完本段內容,,你就會很容易理解為什么女性一直對經(jīng)濟持悲觀態(tài)度。直到密歇根大學調查開始前不久的1974年,,女性才獲得了開設銀行賬戶或申請信貸或貸款的權利,,經(jīng)濟自主權才得到了保障。甚至在20世紀后半葉,,女性還經(jīng)常身處不平等且充滿敵意的工作環(huán)境,。美國最高法院直到1986年才將性騷擾認定為職場性別歧視行為,此時千禧一代中年紀較長的已經(jīng)出生,。女性還要兼顧工作和家庭,,而唯一一部明確致力于幫助女性平衡上述需求的全國性法律《家庭和醫(yī)療休假法》(Family and Medical Leave Act)頒布距今僅三十年。

在這些法律和政策進步的幫助下,,女性得以更好地參與到經(jīng)濟活動中來,,也可以更好地享受經(jīng)濟發(fā)展的成果(這種變化自然也體現(xiàn)在了消費者情緒的變化上)。20世紀80年代,,女性的消費者情緒比男性低12.5%,。到2000年代,這一數(shù)字縮減到了10.2%,。過去兩年,,這一數(shù)字一直保持在5.7%的水平。但事實是,,經(jīng)濟仍舊在按照男性喜好的方式運行,。正因如此,雖然女性創(chuàng)辦了近一半的初創(chuàng)企業(yè),,但女性持有的企業(yè)卻只拿到了不到2%的風投資本,。正因如此,在有數(shù)十億資金流入主要由男性創(chuàng)辦的各種人工智能初創(chuàng)企業(yè)的時候,,育兒勞動力規(guī)模較新冠期間卻幾無改觀,。正因如此,女性工資依然僅為男性的78%(有色人種女性的差距更大),。

現(xiàn)在已經(jīng)到了2024年,。我們有了機器人吸塵器,,手機看一眼就能夠解鎖,還有了太空游客,。但我們生活的社會仍然要求女性在全職工作的同時,,還要全職照顧孩子和年邁的父母,而對女性的支持卻微乎其微,。兩性的消費者情緒差異也可以反映這種“魚與熊掌不可兼得”的困境,。

如果我們不是只在男性對經(jīng)濟與女性一樣悲觀時才關注消費者情緒問題,而是把重點放在提升女性情緒的政策上,,就會怎樣呢,?例如,在2021年年初,,由于女性消費者情緒的提升幅度顯著高于男性,,在“情緒衰退”期間,兩性在消費者情緒方面的差距明顯縮小,。女性消費者情緒為什么會出現(xiàn)這種變化呢,?很可能是因為《美國救援計劃法案》(American Rescue Plan Act)得到了通過。該法案提高了兒童稅收抵免,、兒童保育救援資金標準,,還加強了其他一系列重要的家庭支持項目,這些舉措極大鼓舞了在新冠疫情第一年被迫在照顧家人與有償工作之間做出痛苦選擇的女性,,增強了她們對未來經(jīng)濟穩(wěn)定的信心,。雖然我們不敢說一定是因為這個原因,但鑒于這些計劃的受歡迎程度,,尤其是在女性中的受歡迎程度,包括我們在內,,許多人都認為這種解釋站得住腳,。

在2022年的“情緒衰退”時期,男性和女性的消費者情緒基本為同步變化,,整體消費者情緒在2022年6月跌至谷底,,也是在這個月,通脹水平達到歷史最高,,男性消費者情緒則跌至歷史最低,。2023年,兩性情緒差異再次擴大,。那么2023年發(fā)生了什么呢,?新冠疫情初期匆忙搭建起來的社會安全網(wǎng)宣告解體,工作場所日益恢復“正?!保ǘ栽谶@種“正常狀態(tài)”中一直處于弱勢地位),。盡管我們無法按照種族或殘疾狀況對情緒進行分析,,但其他分析的經(jīng)驗表明,有色人種女性和殘疾女性要想在這樣一個自己受到排斥的體制和國家生存,,必須付出極大的努力,。

筆者想要強調的是,在我們思考和討論經(jīng)濟問題時,,亟需將重點轉向消費者情緒,。但隨著兩性消費者情緒差異的再次出現(xiàn),相關討論再次遭到我們忽視,,這種情況令人擔憂,。雖然許多優(yōu)秀記者已經(jīng)寫過媽媽們在尋找托兒所時所遇到的困難,也介紹過她們在平衡工作與家庭責任時所承受的精神負擔,,但這些討論卻很少成為核心經(jīng)濟話題,。

女性占總人口的一半以上,占總勞動力的將近一半,,還是消費支出重要推手,,但她們對經(jīng)濟的感受卻從未得到足夠重視。這種情況必須改變,。(財富中文網(wǎng))

安維沙·馬朱米德(Anwesha Majumder),,衛(wèi)生科學碩士,是美國全國女性與家庭伙伴組織(National Partnership for Women & Families)的經(jīng)濟學家,。凱瑟琳·加拉格爾·羅賓斯(Katherine Gallagher Robbins),,博士,是全國女性與家庭伙伴組織的高級研究員,。

Fortune.com上發(fā)表的評論文章中表達的觀點,,僅代表作者本人的觀點,不代表《財富》雜志的觀點和立場,。

譯者:梁宇

審校:夏林

Of the numerous economic trends filling column inches over the last few years, few have gained as much traction as the “vibecession.” Coined by Kyla Scanlon in July 2022, the term refers to the phenomenon of people feeling “meh” about the economy despite positive traditional measures of economic health. Much digital ink has been spilled on the topic, including many recent articles declaring the vibecession has moved from hot in 2023 to not in 2024 as consumer sentiment has rebounded in recent months.

But whose feelings have been driving the vibecession in the first place? In a word, men’s.

Men have nearly always felt sunnier about the economy than women have. Our research shows that in the 46 years of the University of Michigan’s monthly Survey of Consumers, men have felt worse than women about the economy just 15 times. While consumer sentiment has been down across the board since the pandemic began, our analysis also shows that a notable, yet undiscussed, aspect of the vibecession conversation was a substantial narrowing of the gender gap between how men and women feel about the economy. The vibecession was not just about everyone feeling bad about the economy–it was also about men finally feeling the same way as women do.

The economy still caters to the wants and needs of men

It’s not hard to imagine why women have been historically pessimistic about the economy. Women were only guaranteed financial autonomy via the right to open bank accounts or apply for credit or loans in 1974, shortly before the survey began. Through the latter half of the 20th century, women frequently faced unequal and hostile conditions on the job. The Supreme Court did not recognize sexual harassment as sex discrimination in the workplace until 1986–within the lifetime of elder millennials. Women also continue to be forced to juggle work and caregiving, with the only national law explicitly focused on helping people balance these demands, the Family and Medical Leave Act, having been on the books for just three decades.

These legal and policy advancements helped make the economy work better for women–and the vibes certainly reflect that. Women’s consumer sentiment was 12.5% lower than men’s in the 1980s. By the 2000s, that gap was 10.2%. Over the last two years, it stands at 5.7%. But the truth of the matter is that the economy still caters to the wants and needs of men. It’s why almost half of all new businesses are started by women, but less than 2% of all venture capital dollars go to women-owned businesses. It’s why billions have been sunk into all manner of artificial intelligence startups largely founded by men, but the childcare workforce has barely recovered from COVID-19. It’s why women continue to be paid 78 cents for every dollar paid to a man and the gaps for women of color are worse.

It’s 2024. We have robot vacuums, phones switch on at a look, and tourists in space. Yet we still live in a society that expects women to work full time while also being full-time caregivers to children and aging parents with minimal support. The persistent gender gap in vibes reflects this impossible bind.

What if, instead of paying attention only when men are feeling as badly about the economy as women are, we focus on policies that lift women’s vibes? For instance, the gap narrowed during the vibecession because women’s perceptions of the economy improved substantially more than men’s in early 2021. What were women reacting to? It’s possible the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act, with its expanded child tax credit, child care rescue funding, and other key family supports buoyed women’s enthusiasm for future financial stability after so many were forced to make painful choices between caregiving and paid work during the first year of the pandemic. Though we can’t say for sure, this seems plausible to us and others given the popularity of these programs, especially for women.

Men’s and women’s vibes moved more or less in tandem throughout 2022, the “vibecession” era, and the overall vibes hit their nadir in June 2022, also the month of highest inflation and the lowest level of consumer sentiment ever recorded for men. The gender vibes gap then grew again in 2023. What happened in 2023? The dissolution of much of the hastily constructed social safety net assembled during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic and workplaces increasingly returning to “normal”–a normal that never worked well for women. And even though we can’t parse the vibes by race or disability status, experience from other analyses suggests women of color and disabled women are struggling mightily to stay afloat in a system and country that were built to exclude them twice and thrice over.

To be clear, focusing on consumer sentiment has been a much-needed shift in how we think and talk about the economy. But turning away from this conversation as the gender vibes gap has resurged is concerning. While many excellent journalists have written about moms’ struggles finding child care or the mental load of balancing work and family responsibilities, those discussions are rarely front and center in the economic conversation.

Women are more than half the population, almost half the workforce, and drive consumer spending–but how they feel about the economy hasn’t been a central part of the conversation. That has to change.

Anwesha Majumder, MHS, is the economist at the National Partnership for Women & Families. Katherine Gallagher Robbins, Ph.D., is a senior fellow at the National Partnership for Women & Families.

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.