臉上的大生意

|

面部識別軟件是一種強大的技術(shù),對公民自由構(gòu)成嚴重的威脅,。與此同時,面部識別也是一個蓬勃發(fā)展的行業(yè),。如今,,數(shù)十家初創(chuàng)企業(yè)和科技巨頭的服務(wù)銷售對象包括酒店、零售店,,甚至學(xué)校和夏令營,。新算法能夠比五年前更精確地識別面部,相關(guān)業(yè)務(wù)也蒸蒸日上,。為了改進算法,,多家公司經(jīng)常在未經(jīng)許可的情況下利用數(shù)十億張面部照片訓(xùn)練。事實上,,你自己的臉就可能在面部識別公司利用的“訓(xùn)練庫”里,,也可能在公司客戶的數(shù)據(jù)庫里。

如果得知一些公司如何獲取面部照片,,消費者可能會吃一驚,。舉例來說,至少三個案例顯示,,科技公司通過人們手機上的照片應(yīng)用程序弄到了數(shù)百萬張圖片,。目前,對面部識別軟件幾乎沒有法律限制,,所以人們也沒有什么辦法阻止公司偷偷使用自己的面部數(shù)據(jù),。

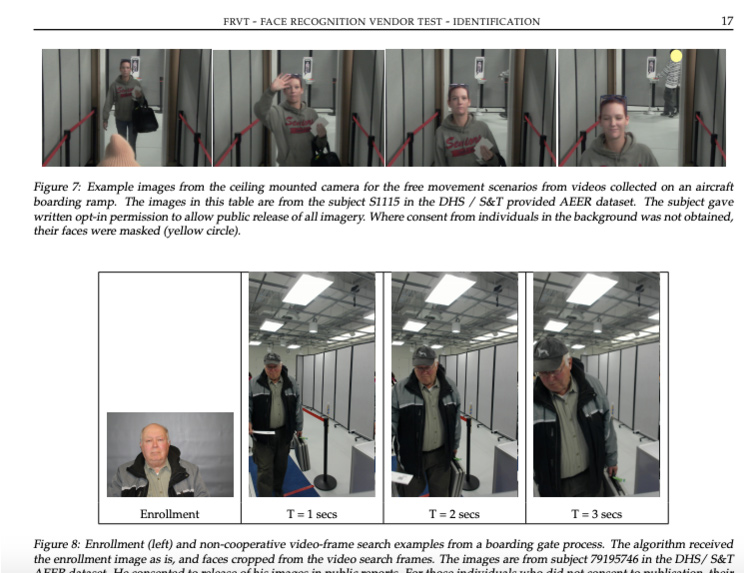

2018年,華盛頓附近的機場廊橋里,,乘客們匆匆走出,,一臺攝像機在附近拍攝人們的臉,。事實上,飛機和乘客都不是真的,。整個場景只是美國國家科學(xué)技術(shù)研究所(NIST)用來演示“在自然環(huán)境下”裝置如何收集面部圖像。收集到的照片也成為NIST反復(fù)提及的競爭優(yōu)勢,,全球各地的公司都可以使用該裝置測試自家的面部識別軟件,。 |

Facial recognition software is a powerful technology that poses serious threats to civil liberties. It’s also a booming business. Today, dozens of startups and tech giants are selling face recognition services to hotels, retail stores—even schools and summer camps. The business is flourishing thanks to new algorithms that can identify people with far more precision than even five years ago. In order to improve these algorithms, companies trained them on billions of faces—often without asking anyone’s permission. Indeed, chances are good that your own face is part of a “training set” used by a facial recognition firm or part of a company’s customer database.

Consumers may be surprised at some of the tactics companies have used to harvest their faces. In at least three cases, for instance, firms have obtained millions of images by harvesting them via photo apps on people’s phones. For now, there are few legal restrictions on facial recognition software, meaning there is little people can do to stop companies using their face in this manner.

In 2018, a camera collected the faces of passengers as they hurried down an airport jetway near Washington, D.C. In reality, neither the jetway nor the passengers were real; the entire structure was merely a set for the National Institute for Science and Technology (NIST) to demonstrate how it could collect faces “in the wild.” The faces would become part of a recurring NIST competition that invites companies across the globe to test their facial recognition software. |

|

在拍攝乘客下機的案例中,志愿者均已經(jīng)同意使用自己的臉,。這也是面部識別早期的方式,。學(xué)術(shù)研究人員在獲得允許之后,才能將拍攝到的面部加入數(shù)據(jù)庫,。如今,,各大公司在面部識別方面更加領(lǐng)先,所以不太可能明確請求使用某些人的臉,,有些公司根本連問都不問,。

包括Face++和Kairos等行業(yè)領(lǐng)袖在內(nèi),各家公司都在面部識別軟件市場競爭,。市場調(diào)研公司Market Research Future稱,,該市場每年增長20%,預(yù)計到2022年將達到每年90億美元,。其商業(yè)模式包括向越來越多的客戶授權(quán)使用軟件,,客戶包括從執(zhí)法部門到零售商等,主要使用識別軟件運行自己的面部識別程序,。

開發(fā)頂尖軟件的競爭中,,勝出的公司必然要算法精確度很高,可以迅速識別面部,,盡量減少所謂誤報,。與人工智能其他領(lǐng)域一樣,要開發(fā)出最好的面部識別算法,,就得收集大量數(shù)據(jù),,也就是面部圖像用來訓(xùn)練。雖然公司經(jīng)批準(zhǔn)后可以使用政府和大學(xué)整理的數(shù)據(jù),,例如耶魯大學(xué)面部數(shù)據(jù)庫,,但相關(guān)數(shù)據(jù)規(guī)模相對較小,面部圖像不超過幾千張,。

官方數(shù)據(jù)還有其他限制,。很多數(shù)據(jù)庫缺乏種族多樣性,或者沒有陰影,、帽子或化妝品等現(xiàn)實世界中可導(dǎo)致面部變化的場景,。為了打造能“在自然環(huán)境中”識別面部的技術(shù),,公司需要更多圖像。要比現(xiàn)在多得多,。

“數(shù)百張不夠,,數(shù)千張也不夠。需要數(shù)百萬的圖像,。如果你不用戴眼鏡的圖像或有色人種圖像訓(xùn)練算法,,結(jié)果不會很準(zhǔn)確?!奔又菝娌孔R別公司FaceFirst的首席執(zhí)行官彼得·特雷普說,。FaceFirst主要幫助零售商識別進入商店的罪犯。 |

In the jetway exercise, volunteers gave the agency consent to use their faces. This is how it worked in the early days of facial recognition; academic researchers took pains to get permission to include faces in their data sets. Today, companies are at the forefront of facial recognition, and they’re unlikely to ask for explicit consent to use someone’s face—if they bother with permission at all.

The companies, including industry leaders like Face++ and Kairos, are competing in a market for facial recognition software that is growing by 20% each year and is expected to be worth $9 billion a year by 2022, according to Market Research Future. Their business model involves licensing software to a growing body of customers—from law enforcement to retailers to high schools—which use it run facial recognition programs of their own.

In the race to produce the best software, the winners will be companies whose algorithms can identify faces with a high degree of accuracy without producing so-called false positives. As in other areas of artificial intelligence, creating the best facial recognition algorithm means amassing a big collection of data—faces, in this case—as a training tool. While companies are able to use the sanctioned collections compiled by government and universities, such as the Yale Face Database, these training sets are relatively small and contain no more than a few thousand faces.

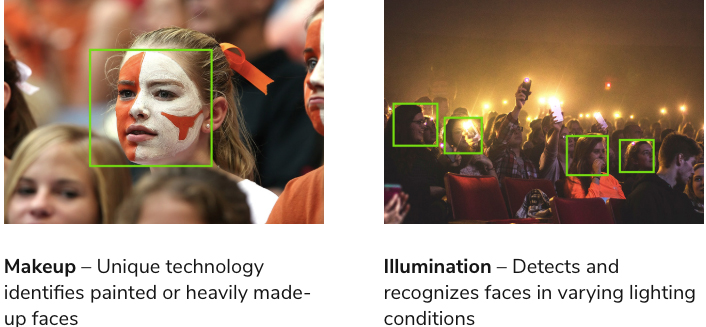

These official data sets have other limitations. Many lack racial diversity or fail to depict conditions—such as shadows or hats or make-up—that can change how faces appear in the real world. In order to build facial recognition technology capable of spotting individuals “in the wild,” companies needed more images. Lots more.

“Hundreds are not enough, thousands are not enough. You need millions of images. If you don’t train the database with people with glasses or people of color, you won’t get accurate results,” says Peter Trepp, the CEO of FaceFirst, a California-based facial recognition company that helps retailers screen for criminals entering their stores. |

****

|

用應(yīng)用程序收集面部圖片

公司從哪可以獲得數(shù)百萬圖像來訓(xùn)練軟件,?來源之一是警方的嫌疑人照片庫,,庫可以從機構(gòu)公開獲取,也有私人公司出售,。例如,,總部位于加利福尼亞州的Vigilant Solutions便提供1500萬張面部圖像的數(shù)據(jù)庫,也是該公司提供面部識別“解決方案”的一部分,。

然而,,一些初創(chuàng)公司發(fā)現(xiàn)了更好的面部圖像來源,即個人相冊應(yīng)用,。類似應(yīng)用可以協(xié)助存儲個人手機上的照片,,通常包含同一個人的各種姿勢,以及在多種環(huán)境下的照片,,為培訓(xùn)算法提供了豐富的數(shù)據(jù)來源,。

“我們的用戶照片包括同一個人在數(shù)千種不同場景里的樣子。站在陰影里,,戴帽子,,各種各樣……”舊金山面部識別公司Ever AI 的首席執(zhí)行官道格·阿萊說,2012年該公司成立時名叫EverRoll,,主要幫用戶管理大量的相冊,。

Ever AI從科斯拉風(fēng)險投資公司和硅谷其他風(fēng)投手里融到了2900萬美元,也參加了最近NIST組織的面部識別競賽,,在“嫌疑犯照片”類別中排名第二,,在“自然環(huán)境中面部”類別排名第三。阿萊認為成功的原因是擁有巨大的照片數(shù)據(jù)庫,,Ever AI估計有130億張照片,。

Ever AI在剛成立時只是個照片應(yīng)用程序,其市場推廣策略非常激進,,引起了爭議,,并導(dǎo)致2016年蘋果把它從應(yīng)用商店下架,。該應(yīng)用最過分的是誘導(dǎo)用戶向所有電話聯(lián)系人發(fā)送推廣鏈接,該策略在硅谷被稱為“增長黑客”,。用戶還指責(zé)應(yīng)用吞掉自己的數(shù)據(jù),。

“剛下載應(yīng)用,第一件事就是收集所有電話號碼,,立即給所有人發(fā)信息……然后就開始收集所有照片并上傳到云端,。” 2015年得克薩斯州肖像工作室老板格雷格·米勒在Facebook上發(fā)表的評論里寫道,。

四年后,米勒沮喪地發(fā)現(xiàn)曾經(jīng)叫Everroll的應(yīng)用程序還是存有自己的照片,,而且搖身一變成了面部識別公司,。

“不,我不知道(應(yīng)用在收集照片),,我一點也不同意,。” 米勒對《財富》雜志說,,“種種現(xiàn)狀說明了一個真正的問題,。再也沒有隱私可言,想到這我真是不寒而栗,?!?/p>

Ever AI的首席執(zhí)行官阿萊表示,公司數(shù)據(jù)庫里不會分享用戶個人信息,,只用照片訓(xùn)練軟件,。他補充說,該公司類似社交媒體網(wǎng)絡(luò),,人們可以選擇退出,。阿萊也否認Ever AI從一開始就想做面部識別,退出現(xiàn)已關(guān)閉的照片應(yīng)用只是商業(yè)決策,。目前,,Ever AI的客戶利用軟件從事一系列活動,包括企業(yè)ID管理,、零售,、電信和執(zhí)法等。

Everroll并不是唯一從照片應(yīng)用轉(zhuǎn)型面部識別的公司,。另一個例子是總部位于舊金山的Orbeus,,2016被亞馬遜悄然收購,該公司曾經(jīng)開發(fā)出很受歡迎的照片管理工具,,叫PhotoTime,。

一位長期在Orbeus工作的員工表示,,該公司的人工智能技術(shù)領(lǐng)先,又擁有大量公共環(huán)境下的用戶照片,,所以成為理想的收購目標(biāo),。

“亞馬遜缺的就是這些,所以全盤收購,,然后關(guān)閉了應(yīng)用程序,。”該員工表示,,他拒絕透露身份,,因為有保密協(xié)議。

如今,,雖然亞馬遜仍在繼續(xù)銷售另一款由Orbeus開發(fā)名為Rekognition的產(chǎn)品,,但當(dāng)初的PhotoTime應(yīng)用已經(jīng)不復(fù)存在。Rekognition也是一款面部識別軟件,,供執(zhí)法部門和其他組織使用,。

至于Orbeus的照片應(yīng)用如何用于訓(xùn)練Rekognition,亞馬遜拒絕透露細節(jié),,只說從各種來源獲取數(shù)據(jù)供面部識別在內(nèi)的人工智能項目使用,。該公司補充說,不會使用Prime會員的照片訓(xùn)練算法,。

另一家使用消費者照片應(yīng)用訓(xùn)練面部識別算法的是Real Networks,。該公司總部位于西雅圖,20世紀90年代曾經(jīng)以在線視頻播放器而聞名,,現(xiàn)在專門開發(fā)能夠在學(xué)校里識別孩子面部的軟件,。該公司還提供一款針對家庭叫RealTimes的智能手機應(yīng)用,一位評論人士表示該應(yīng)用正是獲取面部數(shù)據(jù)的接口,。

“在該應(yīng)用里,,用戶可用自己照片制作視頻幻燈片。想象一下,,媽媽做視頻幻燈片發(fā)送給奶奶,,相關(guān)圖片被用來訓(xùn)練數(shù)據(jù)識別下一代的臉。太可怕了,?!眴讨味卮髮W(xué)教授克萊爾·加維說,他發(fā)表了一篇關(guān)于面部識別技術(shù)頗有影響力的報告,。

Real Networks證實了照片應(yīng)用有助于改進其面部識別工具,,但補充說也使用了其他數(shù)據(jù)源。

在公司使用照片應(yīng)用獲取面部照片訓(xùn)練數(shù)據(jù)的各種案例里,都沒有明確征求消費者的許可,。相反,,各公司似乎通過服務(wù)協(xié)議獲得了法律許可。

然而,,比起其他一些面部識別公司,,利用照片應(yīng)用獲取數(shù)據(jù)的公司已經(jīng)算得上很努力。在NIST負責(zé)面部識別競賽的帕特里克·格洛特說,,面部識別公司通常會編寫一些程序,,從SmugMug或Tumblr之類網(wǎng)站直接“抓取”圖片。此類情況下,,公司更沒有必要向面部照片被用于訓(xùn)練數(shù)據(jù)的用戶征求同意,。

最近,美國國家廣播公司(NBC)的一篇報道重點批評了類似的“自助抓取”做法,,道詳細描述了IBM如何從照片共享網(wǎng)站Flickr中抓走超過100萬張面部照片,,用作人工智能研究。(IBM研究部門負責(zé)人工智能技術(shù)的約翰·史密斯告訴NBC,,該公司將努力“保護個人隱私”,,只要有人希望刪除自己的數(shù)據(jù),,都會積極配合,。)

面對種種情況,人們不禁產(chǎn)生疑問,,各公司如何保護收集的面部數(shù)據(jù),,政府是否應(yīng)該加強監(jiān)督。隨著面部識別在社會上的更多領(lǐng)域里應(yīng)用,,推動大小公司業(yè)務(wù)發(fā)展,,相關(guān)問題也更加緊迫。 |

An App for That

Where might a company obtain millions of images to train its software? One source has been databases of police mug shots, which are publicly available from state agencies and are also for sale by private companies. California-based Vigilant Solutions, for instance, offers a collection of 15 million faces as part of its facial recognition “solution.”

Some startups, however, have found an even better source of faces: personal photo album apps. These apps, which compile photos stored on a person’s phone, typically contain multiple images of the same person in a wide variety of poses and situations—a rich source of training data.

“We have consumers who tag the same person in thousands of different scenarios. Standing in the shadows, with hats-on, you name it,” says Doug Aley, the CEO of Ever AI, a San Francisco facial recognition startup that launched in 2012 as EverRoll, an app to help consumers manage their bulging photo collections.

Ever AI, which has raised $29 million from Khosla Ventures and other Silicon Valley venture capital firms, entered NIST’s most recent facial recognition competition, and placed second in the contest’s “Mugshots” category and third in “Faces in the Wild.” Aley credits the success to the company’s immense photo database, which Ever AI estimates to number 13 billion images.

In its earlier days, when Ever AI was a mere photo app, its aggressive marketing practices created controversy and temporarily led Apple to ban EverRoll from the App Store in 2016. Notably, the app induced users to send promotional links to all of their phone contacts, a tactic known as “growth hacking” in Silicon Valley parlance. Users also accused it of gobbling their data.

“The first thing it does even as it is installing is to harvest all your phone numbers and immediately message everybody… This thing then starts to pull all your photos and put them into the cloud,” wrote Greg Miller, a Texas-based portrait studio owner, in a 2015 Facebook review.

Four years later, Miller was dismayed to discover that the app once known as EverRoll still had his photos, and that it was now a facial recognition company.

“No, I was not aware of that, and I don’t agree with it one bit,” Miller tells Fortune. “All of this being tracked is a real problem. Nothing is private anymore and that just scares the hell out of me.”

Aley, the Ever AI CEO, says the company doesn’t share identifying information about individuals in its database, and only uses the photos to train its software. He added the company is akin to a social media network from which people can opt out. Aley also denied that Ever AI had intended to become a facial recognition company from the get-go, saying the move away from the now-shuttered photo app was a business decision. Currently, Ever AI’s customers are using it for a range of activities, including corporate ID management, retail, telecommunications, and law enforcement.

EverRoll is not the only facial recognition company that once offered a consumer photo app. Another example is Orbeus, a San Francisco-based startup quietly acquired by Amazon in 2016, which once offered a popular picture organizer called PhotoTime.

According to a longtime Orbeus employee, the startup’s A.I. technology and its large collection of photos with people in public settings made it an appealing acquisition target.

“Amazon was looking for that capability. They acquired everything, then shut down the app,” says the employee, who declined to be identified, citing non-disclosure agreements.

Today the PhotoTime app no longer exists, though Amazon continues to sell another Orbeus product known as Rekognition. The product is a type of facial recognition software used by law enforcement and other organizations.

Amazon declined to provide details about the extent to which Orbeus’s photo app was used to train the Rekognition software, only stating it obtains data for its A.I. projects, including facial recognition, from a variety of sources. The company added it does not use its customers’ Prime photo service to train its algorithms.

Another company that uses a consumer photo app to train its facial recognition algorithm is Real Networks. The Seattle-based company, once known for its 1990s-era online video player, today specializes in software that can recognize children’s faces in schools. At the same time, it offers a smartphone app aimed at families called RealTimes, which one critic says has served as a pretext to obtain facial data.

“The app allows users to make video slideshows of their own photos. Imagine mom putting together a video slide show to send to grandma, and those images being used to train a dataset to use on young faces. It’s pretty horrible,” says Clare Garvie, a Georgetown University professor who published an influential report on facial recognition technology.

Real Networks confirmed the photo app helps improve its facial recognition tool, but added that it uses additional data sources for the purpose.

In all of these cases where companies used a photo app to harvest faces for training data, they didn’t ask for consumers’ explicit permission. Instead, the firms appear to have obtained legal consent through their terms of service agreements.

This is, however, more than what some other facial recognition companies have done. According to Patrick Grother, who runs the face competitions at NIST, it’s common for facial recognition companies to write programs that “scrape” pictures from websites like SmugMug or Tumblr. In these cases, there is not even a pretext of consent from those whose faces end up in training sets.

This “help yourself” approach was underscored by a recent NBC News report detailing how IBM siphoned more than one million faces from the photo sharing site Flickr as part of the company’s artificial intelligence research. (John Smith, who oversees AI technology for IBM’s research division, told NBC News that the company was committed to “protecting the privacy of individuals” and would work with those who sought removal from the dataset.)

All of this raises questions about what companies are doing to safeguard the facial data they collect, and whether governments should provide more oversight. The issues will only be become more pressing as facial recognition spreads to more areas of society, and powers the business of companies large and small. |

****

|

從商店到學(xué)校

面部識別軟件并不是新鮮事物,。20世紀80年代美國數(shù)學(xué)家開始將人臉定義為一系列數(shù)值,,用概率模型尋找匹配時,該技術(shù)的原始版本就已經(jīng)存在,。在2001年的橄欖球冠軍賽超級碗上,,佛羅里達州坦帕市的保安人員便已應(yīng)用,賭場則已經(jīng)使用多年,。但過去幾年里情況出現(xiàn)了變化,。

“面部識別正經(jīng)歷一場革命?!?NIST的格洛瑟表示,。他補充說,快速閃過或像素差的圖像提升最大?!盎A(chǔ)技術(shù)已經(jīng)改變,。舊技術(shù)已經(jīng)被新一代算法取代,而且非常有效,?!?/p>

面部識別的革命得益于廣泛改變?nèi)斯ぶ悄茴I(lǐng)域的兩大因素。第一項因素是新興的深度學(xué)習(xí)科學(xué),,模仿人腦的模式識別系統(tǒng),。第二項因素則是史無前例的海量數(shù)據(jù),借助云計算可以實現(xiàn)低成本存儲解析數(shù)據(jù),。

毫無疑問,,最先充分利用各項新技術(shù)的公司是谷歌和Facebook。2014年,,社交網(wǎng)絡(luò)Facebook推出了名叫DeepFace的項目,,可以識別兩張臉是否屬于同一個人,準(zhǔn)確率為97.25%,,與人類水平相當(dāng),。安全公司Gemalto的數(shù)據(jù)顯示,一年后谷歌的facenet程序準(zhǔn)確率達100%,。

如今,,谷歌、Facebook和微軟等其他科技巨頭在面部識別方面都處于領(lǐng)先地位,,主要原因是巨頭擁有龐大的面部數(shù)據(jù)庫,。不過,隨著越來越多的初創(chuàng)公司在逐漸增長的面部識別軟件市場上尋找突破,,識別準(zhǔn)確度方面得分也很高,。

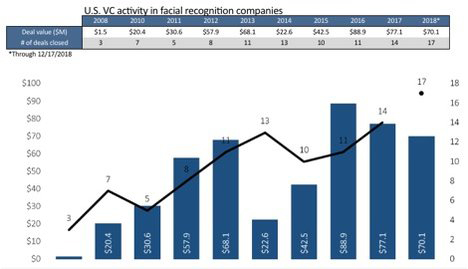

僅在美國就有十幾家從事該業(yè)務(wù)的初創(chuàng)公司,其中包括Kairos和FaceFirst,。市場研究公司PitchBook稱,,硅谷正在扎堆進入該行業(yè),該公司還披露了過去幾年發(fā)生的數(shù)十宗投資交易,。據(jù)PitchBook的數(shù)據(jù)顯示,,過去三年平均總投資金額7870萬美元。按照硅谷標(biāo)準(zhǔn),,這一數(shù)字算不上太亮眼,,但能夠看出風(fēng)險投資人在下重注賭其中一些初創(chuàng)公司會迅速成長為大公司。 |

From Shops to Schools

Facial recognition software is not new. Primitive versions of the technology have existed since the 1980s when American mathematicians began defining faces as a series of numerical values, and used probability models to find a match. Security personnel in Tampa, Fla. deployed it at the 2001 Super Bowl and casinos have used it for years. But in the last few years, something changed.

“Facial recognition is undergoing something of a revolution,” says Grother of NIST, adding the change is most pronounced with fleeting or poor quality images. “The underlying technology has changed. The old tech has been replaced by a new generation of algorithms, and they’re remarkably effective.”

This revolution in facial recognition comes thanks to two factors that are transforming the field of artificial intelligence more broadly. The first is the emerging science of deep learning, a pattern recognition system that resembles the human brain. The second is an unprecedented glut of data that can be stored and parsed at low cost with the aid of cloud computing.

The first companies to take full advantage of these new developments, unsurprisingly, were Google and Facebook. In 2014, the social network launched a program called DeepFace that could discern if two faces belonged to the same person with an accuracy rate of 97.25%—a rate equivalent to what humans scored on the same test. A year later, Google topped this with its FaceNet program, which obtained a 100% accuracy score, according to security firm Gemalto.

Today, those companies and other tech giants like Microsoft are leaders in facial recognition—in no small part because of their access to large databases of faces. A growing number of startups, though, are also posting high accuracy scores as they seek a niche in a growing market for face software.

In the U.S. alone, there are more than a dozen such startups, including Kairos and FaceFirst. Silicon Valley has been flocking to the sector, according to market researcher PitchBook, which reveals dozens of investment deals taking place in the last few years. The average total investment in the last three years is $78.7 million, according to PitchBook. This is not an eye-popping number by Silicon Valley standards, but reflects a significant bet by venture capitalists that at least a few facial recognition startups will mushroom into major companies. |

|

面部識別公司的商業(yè)模式仍然在不斷出現(xiàn)?,F(xiàn)在多數(shù)公司的模式為授權(quán)一些組織機構(gòu)使用軟件,。根據(jù)Crunchbase的數(shù)據(jù),,Ever AI和FaceFirst之類的初創(chuàng)公司的年收入尚可,從200萬美元到800萬美元不等,。同時,,亞馬遜和其他科技巨頭沒有透露收入當(dāng)中有多少來自于面部識別軟件使用許可費。

多年來,,最愿意為面部識別付錢的客戶是執(zhí)法機構(gòu),。不過,最近越來越多的組織,,包括沃爾瑪也在使用此類軟件識別了解走進實體店的人,。

加州的FaceFirst客戶情況也差不多,其主要銷售對象為數(shù)百家零售商,,包括一美元店和藥店等,。該公司的首席執(zhí)行官特雷普說,大部分客戶使用該技術(shù)識別進店的犯罪分子,,不過零售商也有其他目的,,例如識別VIP客戶或員工。

與此同時,,看起來亞馬遜正在努力為面部識別尋找商業(yè)模式,。有報道稱,亞馬遜除了向警察部門出售使用許可,,也跟酒店合作加快辦理入住手續(xù),。

“各地的公司都來找亞馬遜說:‘希望你們實現(xiàn)這項功能?!璐宋覀兙蜁l(fā)現(xiàn)最合適的機會,。興趣真是各種各樣,?!眮嗰R遜收購面部識別公司Orbeus時加入亞馬遜的一位匿名人士表示。

就亞馬遜而言,,種種努力并非毫無爭議,。去年7月,美國公民自由聯(lián)盟對其軟件進行了測試,,根據(jù)重罪犯人數(shù)據(jù)庫測試識別國會議員的臉,。結(jié)果錯誤識別了28次,其中大多數(shù)涉及有色人種議員,。作為回應(yīng),,美國公民自由聯(lián)盟呼吁禁止執(zhí)法人員使用面部識別技術(shù)。與此同時,,亞馬遜的員工也向公司施壓,,要求證明向警察部門以及美國移民和海關(guān)執(zhí)法部門銷售軟件的正當(dāng)性。

美國國會的一些成員,包括眾議員杰羅德·納德勒(紐約州)和參議員羅恩·懷登(俄勒岡州),,已經(jīng)要求政府問責(zé)辦公室調(diào)查面部識別軟件的使用,。企業(yè)領(lǐng)導(dǎo)人也對該技術(shù)的應(yīng)用感到不安,其中包括微軟總裁布拉德·史密斯,,去年12月他也曾經(jīng)呼吁政府出手監(jiān)管,。

即便外界越發(fā)關(guān)注,公司還是能夠找到新的應(yīng)用場景實現(xiàn)銷售,,面部識別技術(shù)也隨之不斷擴大應(yīng)用范圍,。其中就包括家庭照片應(yīng)用開發(fā)商Real Networks,目前該公司向全美國的K-12學(xué)校免費提供軟件,。公司表示有數(shù)百所學(xué)校正在使用,。在接受《連線》雜志采訪時,該公司的首席執(zhí)行官羅布·格拉澤說,,之所以推進該計劃,,是為了解決有關(guān)學(xué)校安全和槍支管制的爭論而采取的非黨派解決方案。目前,,Real Networks的網(wǎng)站正在宣傳其技術(shù),,宣稱活動主持人可用來“識別每位粉絲、客戶,、員工或客人”,,哪怕臉遮住了也能夠認出來。 |

Business models for facial recognition companies are still emerging. Today, most revolve around licensing software to organizations. According to data from Crunchbase, annual revenue for startups like Ever AI and FaceFirst is relatively modest, ranging from $2 million to $8 million. Amazon and the other tech giants, meanwhile, have not disclosed how much of their revenue comes from licensing facial recognition.

For years, the most avid paying customers for facial recognition has been law enforcement agencies. More recently, though, a growing number of organizations, including Wal-Mart, are using the software to identify and learn more about the people who enter their physical premises.

This is certainly the case for customers of California-based FaceFirst, which sells facial recognition software to hundreds of retailers, including dollar stores and pharmacies. Its CEO, Trepp, says the bulk of his clients use the technology to screen for criminals coming into their stores but, increasingly, retailers are testing it for other purposes such as recognizing VIP customers or identifying employees.

Amazon, meanwhile, appears to be casting a wide net in its efforts to find a business models for face recognition. In addition to selling to police departments, the retail giant is reportedly working with hotels to help them expedite check-in procedures.

“Companies from all over are coming to Amazon and saying, ‘This what we’d like you to do’. Then you figure out that’s your sweet spot. The interest is all over the place,” says the unnamed person who joined Amazon when the company acquired Orbeus, the facial recognition firm.

These efforts, in the case of Amazon, have not been without controversy. Last July, the ACLU tested the company’s software by running the faces of every member of Congress against a database of convicted felons. The test resulted in 28 false positives, the majority of which comprised Congressional members of color. In response, the ACLU called for a ban on the use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement. Meanwhile, Amazon’s own employees have pressed the company to justify the sale of the software to police departments and to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Some members of Congress, including Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), have since asked the Government Accountability Office to investigate the use of facial recognition software. Corporate leaders are also uneasy about the technology’s applications. Among them: Microsoft president Brad Smith, who in December called for government regulation.

But even as concern mounts, use of facial recognition technology is expanding as companies find new and novel applications for which to sell it. These include Real Networks, the maker of the family photo app, which is offering its software for free to K-12 schools across the country. The company says hundreds of schools are now using it. In an interview with Wired magazine, CEO Rob Glaser says he began the initiative as a non-partisan solution to the debate over school safety and gun control. Currently, Real Networks’ website is touting its technology as a way for event hosts to “recognize every fan, customer, employee, or guest”—even if their face is covered. |

|

Real Networks并不是唯一針對兒童開發(fā)面部識別產(chǎn)品的公司,。得克薩斯州的一家初創(chuàng)公司W(wǎng)aldo正在向數(shù)百所學(xué)校以及兒童運動聯(lián)盟和夏令營提供技術(shù),。實際應(yīng)用時,要使用Waldo的軟件掃描攝像機或官方攝影師拍攝的圖像,,然后將孩子的臉與父母提供的圖像數(shù)據(jù)庫匹配,。不愿參與的父母可以選擇退出。

首席執(zhí)行官羅德尼·賴斯說,,學(xué)校每年都要拍攝數(shù)萬張照片,,年鑒上只能夠看到少數(shù)幾張。他說,,面部識別是一種有效的方法,,可以將剩下部分的照片發(fā)給想要的人。

“可以不用再買爆米花或禮物了,,不如送給孩子的祖父母一系列照片,。”他解釋說,,Waldo跟公立學(xué)校有一半一半的收入分成協(xié)議,。目前該服務(wù)已經(jīng)拓展到美國30多個州,。

Waldo和FaceFirst的發(fā)展表明了,企業(yè)如何推動面部識別正?;?,就在不久前這些還只是科幻小說里的內(nèi)容。隨著技術(shù)傳播到美國經(jīng)濟的更多領(lǐng)域,,越來越多公司將收集我們的面孔,,要么訓(xùn)練算法,要么用來辨識顧客和罪犯,,雖然犯錯或濫用的可能性也在增加,。 |

Real Networks isn’t the only facial recognition company with products that focus on children. A Texas-based startup called Waldo is supplying the technology to hundreds of schools, as well as kids’ sports leagues and summer camps. In practice, this involves using Waldo’s software to scan images taken by video cameras or official photographers, then match children’s faces to a database of images provided by parents. Those parents who don’t wish to participate can opt out.

According to CEO Rodney Rice, schools take tens of thousands of photos every year and only a handful of them up being seen in a yearbook. Facial recognition, he says, is an efficient way to distribute the remaining ones to those who would like to have them.

“Instead of buying popcorn or wrapping paper, you can get a photo stream to your kids’ grandparents,” says Rice, explaining that Waldo has a 50-50 revenue sharing arrangement with public schools. The service is now doing business in more than 30 U.S. states.

The growth of Waldo and FaceFirst show how businesses are helping to normalize facial recognition, which not long ago was the stuff of science fiction. And as the technology spreads to more sectors of the American economy, more companies will collect copies of our faces—either to train their algorithms or to recognize customers and criminals—even as the potential for mistakes or misuse grow. |

****

|

臉上的未來

2017年播出的技術(shù)反烏托邦電視劇《黑鏡》(Black Mirror)里,一位焦慮的母親看到女兒跟小混混在一起的畫面,,非常擔(dān)心,。為了確認身份,她將男孩的面部圖像上傳到用戶面部識別服務(wù),。軟件立即顯示了男孩的名字和工作地點,,然后她找過去對質(zhì)。

曾經(jīng)遙不可及的情景,,如今已經(jīng)近在咫尺,。盡管人們對面部識別的擔(dān)憂主要集中在政府使用上,但私人公司甚至個人的“黑鏡式”利用也將造成明顯的隱私風(fēng)險,。

隨著越來越多的公司開始銷售面部識別技術(shù),,人們的面部數(shù)據(jù)進入更多的數(shù)據(jù)庫,偷窺者和跟蹤者也可能用上新技術(shù),。商人和房東也能夠用來識別不受歡迎的人,,悄悄地拒絕提供住房或服務(wù)。

“凡是有攝像機和大量人流的地方,,都可以開始積累圖像數(shù)據(jù)庫,,然后用分析軟件查看是否與既有數(shù)據(jù)庫匹配?!?美國公民自由聯(lián)盟的政策分析師杰伊·斯坦利表示,。

此外也存在黑客攻擊的風(fēng)險,。網(wǎng)絡(luò)安全公司Gemini Advisors的安德雷·巴雷舍維奇說,,曾經(jīng)見過從印度國家生物特征數(shù)據(jù)庫中竊取的資料,都在“暗網(wǎng)”上出售,。他還沒發(fā)現(xiàn)有人出售美國人面部數(shù)據(jù)庫,,但補充說,“這只是時間問題,?!比绻l(fā)生這種情況,,從酒店或零售商盜取的顧客面部圖片可以幫助罪犯實施詐騙或冒充身份。

隨著技術(shù)在幾乎沒有政府監(jiān)管的情況不斷推廣,,限制濫用的最大希望可能在于軟件開發(fā)商自身,。在接受《財富》雜志采訪時,面部識別初創(chuàng)公司的首席執(zhí)行官們都表示,,對隱私風(fēng)險有著深刻的認識,。包括FaceFirst首席執(zhí)行官在內(nèi)不少人認為,中國面部監(jiān)控系統(tǒng)普及比較有警示意義,。

首席執(zhí)行官們還提出兩種方法限制行業(yè)濫用技術(shù),。第一是與購買軟件者密切合作,確??蛻舨粫S意使用,。舉例來說,Ever AI的阿萊便表示,,公司遵循的標(biāo)準(zhǔn)比亞馬遜更高,,他聲稱亞馬遜幾乎向所有客戶出售Rekognition軟件。

為了回應(yīng)如何管理濫用的問題,,亞馬遜提供了馬特·伍德之前發(fā)表的一份聲明,。馬特·伍德在亞馬遜云服務(wù)平臺負責(zé)人工智能服務(wù),他指出公司政策禁止非法或有害行為,。

負責(zé)面部識別業(yè)務(wù)高管還提到另一項潛在的隱私保護措施,,使用技術(shù)措施確保數(shù)據(jù)庫中識別的面部不會遭到黑客攻擊。

Waldo公司的首席執(zhí)行官賴斯表示,,面部圖像是以字母數(shù)字散列的形式存儲,。也就是說,即使發(fā)生數(shù)據(jù)泄露,,人們的隱私也不會受到影響,,因為黑客將無法使用散列的面部圖像重建面部并對應(yīng)身份。其他人表示同意,。

賴斯還擔(dān)心,,立法者制定面部識別技術(shù)使用規(guī)則,可能弊大于利,?!鞍押⒆雍拖丛杷黄鸬钩鋈ィ贫ㄒ恍┋偪竦囊?guī)定,,都差不多,,最后只會是鬧劇?!彼f,。

與此同時,,一些開發(fā)面部識別軟件的公司也在應(yīng)用新技術(shù),可能不再需要大量收集面部圖片訓(xùn)練算法,??偛课挥谶~阿密的面部識別初創(chuàng)公司Kairos便是其中之一,其客戶包括一家大型連鎖酒店,。首席安全官斯蒂芬·摩爾表示,,Kairos正在打造“合成”面部數(shù)據(jù),復(fù)制各種表情和照明條件下的面部,。他說,,“人造面孔”意味著公司開發(fā)產(chǎn)品時需要的數(shù)據(jù)庫規(guī)模可以小一些,。

不管是監(jiān)督面部識別軟件客戶,,還是保障數(shù)據(jù)安全,打造綜合培訓(xùn)工具,,各項措施都可以將企業(yè)使用人們面部圖像的問題緩和一些,。與此同時,F(xiàn)aceFirst的特雷普相信隨著人們對該技術(shù)越發(fā)熟悉,,相關(guān)焦慮也會減少,。他甚至認為2002年科幻電影《少數(shù)派報告》當(dāng)中出現(xiàn)的面部識別場景會變得很正常。

“千禧一代更愿意提供面部圖像,?!渡贁?shù)派報告》里呈現(xiàn)的世界即將到來?!彼f,。“如果做得好,,人們將享受到便利,,而且將變成積極的經(jīng)歷。不會感覺太古怪,?!?/p>

包括美國公民自由聯(lián)盟在內(nèi)的其他方面則沒有那么樂觀。不過,,盡管有關(guān)該技術(shù)的爭論日益激烈,,目前幾乎沒有任何法律限制使用面部數(shù)據(jù)。例外只有伊利諾斯州,、得克薩斯州和華盛頓州,,三個州里使用某人的臉之前需要一定程度的同意。相關(guān)法律并未真正檢驗過,,只有一地例外:伊利諾伊州,,該州的消費者可提起訴訟行使權(quán)利。

目前,,伊利諾伊州的法律也是一起與Facebook有關(guān)的,、備受關(guān)注的上訴法院案件主題,該案聲稱,,獲取面部的限制并不能延伸到數(shù)字掃描,。2017年,F(xiàn)acebook和谷歌進行了一場失敗的游說活動,,希望說服伊利諾伊州的議員降低法律的影響,。1月底,伊利諾伊州最高法院裁定,,如果消費者想就未經(jīng)授權(quán)識別生物特征提起訴訟,,無須證明在現(xiàn)實世界中受到傷害,進一步鼓勵了該法律的支持者,。

其他國家也在考慮制定生物識別方面的法律,。在聯(lián)邦一級,目前立法者還很少關(guān)注,。然而情況可能會發(fā)生變化,,因為參議員布萊恩·沙茨(夏威夷州)和羅伊·布朗特(密蘇里州)在3月提出了一項法案,要求公司在公共場所使用面部識別功能和/或與第三方共享面部數(shù)據(jù)之前,,必須獲得許可,。

喬治敦大學(xué)的研究員加維支持由法律監(jiān)督該項技術(shù)。但她也表示立法者很難跟上技術(shù)發(fā)展的腳步,。

“面部識別面臨的一項挑戰(zhàn)是,,由于傳統(tǒng)數(shù)據(jù)庫存在,其吸收速度非???。人們的面部圖片太容易被采集到了?!彼f,。“跟指紋不一樣的是,,長期以來指紋采集的方式和時間一直有規(guī)則限制,,而面部識別技術(shù)領(lǐng)域沒有規(guī)則?!保ㄘ敻恢形木W(wǎng)) 譯者:馮豐 審校:夏林 |

The Future of Your Face

In a 2017 episode of the techno-dystopian TV series Black Mirror, an anxious mother frets over images of a ne’er-do-well carrying on with her daughter. To identify him, she uploads an image of his face to a consumer facial identification service. The software promptly displays his name and place of work, and she goes to confronts him.

Such a scenario, once far-fetched, feels close at hand today. While fears over facial recognition have focused on its use by governments, its deployment by private companies or even individuals—Black Mirror-style—poses obvious privacy risks.

As more companies start to sell facial recognition, and as our faces end up in more databases, the software could catch on with voyeurs and stalkers. Merchants and landlords could also use it to identify those they deem to be undesirable, and quietly withhold housing or services.

“Anybody with a video camera and a place with a lot of foot traffic can start to compile a databases of images, and then use this analytic software to see if there’s a match with what you’ve compiled,” says Jay Stanley, a policy analyst of the ACLU.

There’s also the risk of hacking. Andrei Barysevich of Gemini Advisors, a cybersecurity firm, says he has seen profiles stolen from India’s national biometrics database for sale on “dark web” Internet sites. He has yet to see databases of American faces for sale, but added, “It’s just a matter of time.” If such a thing were to occur, a stolen collection of customer faces from a hotel or retailer could help criminals carry out fraud or identity theft.

As the technology spreads with little government oversight, the best hope to limit its misuse may lie with the software makers themselves. In interviews with Fortune, the CEOs of facial recognition startups all stated they were deeply attuned to privacy perils. A number, including the CEO of FaceFirst, cited the spread of face surveillance systems in China as a cautionary tale.

The CEOs also offered two ways the industry can limit misuse of their technology. The first is by working closely with the purchasers of their software to ensure clients don’t deploy it willy-nilly. Aley of Ever AI, for instance, says his company follows a higher standard than Amazon, which he claims furnishes its Rekognition tool to nearly all comers.

In response to a question of how it polices misuse, Amazon provided a previously published statement by Matt Wood, who overseas artificial intelligence services at Amazon Web Services, pointing to a company policy prohibiting activity that is illegal or harmful to others.

The other potential privacy safeguard cited by facial recognition executives is the use of technical measures to ensure the faces identified in their databases can’t be hacked.

Rice, the CEO of the Waldo, says faces are stored in the form of alphanumeric hashes. This means that, even in the event of a data breach, privacy would not be compromised because a hacker would not be able to use the hashes to reconstruct the faces and their identities. The point was echoed by others.

Rice is also wary that lawmakers could do more harm than good by making rules for the use of facial technology. “Throwing the baby out with the bathwater, and creating a bunch of crazy regulations, that would be a travesty,” he says.

Meanwhile, some companies that make facial recognition software are using new techniques that may reduce the need for large collections of faces to train their algorithms. This is the case with Kairos, a Miami-based facial recognition startup that names a major hotel chain among its clients. According to chief security officer Stephen Moore, Kairos is creating “synthetic” facial data to replicate a wide variety of facial expressions and lighting conditions. He says these “artificial faces” means the company can rely on smaller sets of real world faces to build its products.

All of these measures—oversight of facial recognition customers, sound data security, and synthetic training tools—could allay some of the privacy concerns related to companies’ use of our faces. At the same time, Trepp of FaceFirst believes anxiety over the technology will diminish as we become more familiar with it. He even argues that facial recognition scenes in the 2002 sci-fi movie Minority Report will start to feel normal.

“Millennials are much more willing to hand over their face. That [Minority Report] world is coming,” he says. “Done properly, I think people are going to enjoy it and it’s going to be a positive experience. It won’t feel creepy.”

Others, including the ACLU, are less sanguine. Still, despite the growing controversy around the technology, there is, for now, almost nothing in the way of laws to limit the use of your face. The only exception comes from a trio of states—Illinois, Texas, and Washington—that require a degree of consent before the use of someone’s face. These laws have not really been tested, with one exception: Illinois, where consumers can bring lawsuits to enforce the right.

Currently, the Illinois law is the subject of a high profile appeals court case involving Facebook, which claims that restrictions on obtaining faces does not extend to digital scans. In 2017, Facebook and Google ran an unsuccessful lobbying campaign to persuade Illinois lawmakers to dilute the law. In late January, the law’s supporters got a boost when the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that consumers do not have to show real-world harm if they want to sue over the unauthorized use of their biometrics.

Other states are considering biometrics laws of their own. At the federal level, lawmakers have so far devoted little attention to the matter. This may be changing, however, as Senators Brian Schatz (D-Ha.) and Roy Blount (R.MO) this month introduced a bill that would require companies to get permission before using facial recognition in public places and or share face data with third parties.

Garvie, the Georgetown researcher, is in favor of laws to oversee the technology. But she says it has been difficult for lawmakers to keep up.

“One challenge of facial recognition is it’s been incredibly quick on the uptake because of legacy databases. There are so many instances where our faces were captured,” she says. “Unlike fingerprints, where there have long been rules on how and when they’re collected, there are no rules for face technology.” |

?