摩根大通在底特律:美國(guó)版的“精準(zhǔn)扶貧”故事

|

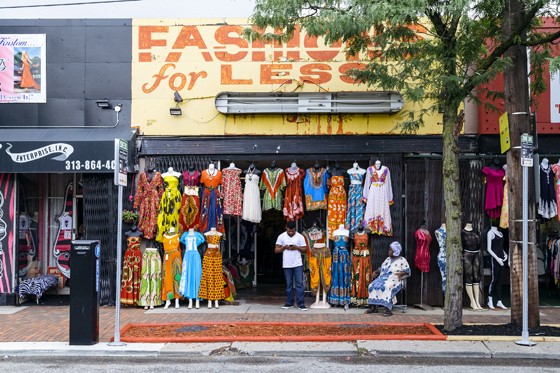

在底特律的西麥克尼克斯路上只有兩種店面:一種是關(guān)門(mén)的,,另一種是“它怎么還沒(méi)關(guān)門(mén),?”的。道路兩旁的一二層鋪面要么用褐色的木板封著,,要么拉下了煙灰色的卷閘門(mén),。星期四上午10點(diǎn)半,十字路口的那家售酒店是唯一有點(diǎn)人流量的地方——當(dāng)然,,如果你沒(méi)算那起路邊的交易。一個(gè)開(kāi)著本田小轎車(chē)的大叔將車(chē)子停在公交站牌前面,,跟一個(gè)行人用現(xiàn)金交易一袋用三明治袋子裝著的東西,,全然不顧一輛30路公交車(chē)在后面按喇叭。 對(duì)于沒(méi)有生活在底特律的人來(lái)說(shuō),,他們想象中的底特律,,大概就是這個(gè)樣子了。這也難怪,,每當(dāng)你在報(bào)紙上看到底特律的人口已經(jīng)比二戰(zhàn)后減少了60%,,或是在網(wǎng)上看到底特律大騷亂50周年的紀(jì)念專(zhuān)題時(shí),你腦中肯定會(huì)想象出類(lèi)似的畫(huà)面,。這符合標(biāo)準(zhǔn)的“鐵銹地帶”的形象——昔日繁華的工業(yè)區(qū)變成一片廢墟,,城市一片死氣,值得慶幸的無(wú)非是這些關(guān)張的店面還沒(méi)有被人打砸搶燒罷了,。 然而真正的底特律,,以及這條麥克尼克斯路,并非是這樣死氣沉沉的末日景象,。與附近的利沃諾斯大道一樣,,麥克尼克斯路也是住宅區(qū)的一條主干道,它基本上安然無(wú)恙地挺過(guò)了芝加哥的歷次重大風(fēng)波。在步行所及的范圍里,,有幾千戶(hù)中等收入家庭,。離此不到六個(gè)街區(qū),坐落著兩座大學(xué)和一家醫(yī)院,,這些都是能給出不錯(cuò)的薪水的“鐵飯碗”單位,。 |

There are two kinds of storefronts on this stretch of Detroit’s West ?McNichols Road: Boarded-up and “Why isn’t this boarded up?” Most of the one- and two-story buildings are clad in drab painted plywood or the gunmetal gray of security shutters. At 10:30 on a Thursday morning, the liquor store on the corner of San Juan is the only business with noticeable traffic—?unless you count the one being run out of the Honda coupe idling at a bus stop. The driver is conducting a cash-for--something-in-a-sandwich-bag transaction with a passerby, both of them oblivious to the horn blasts from the westbound Number 30 whose space they occupy. It’s a tableau that epitomizes what people who don’t live in Detroit imagine when they think about Detroit. It’s the picture you might conjure when you read that the city’s population has shrunk by 60% since World War II, or when you see 50th-anniversary remembrances of the riots of 1967. It’s an almost-perfect image of Rust Belt stagnation; the only detail missing from the stereotype is that none of the shuttered stores is actually on fire. But the real Detroit is not a blank canvas for apocalyptic visions of decline—and neither is McNichols Road. Along with nearby Livernois Avenue, McNichols is a main artery of a residential area that has stayed healthy through all of Detroit’s well-publicized woes. It’s within walking distance of thousands of middle-income households—and within six blocks of two college campuses and a hospital, “anchor employers” supporting decent-paying jobs. |

|

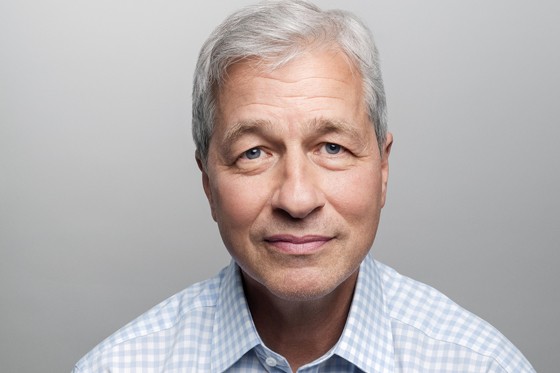

現(xiàn)在,,有些底特律人想把這個(gè)沒(méi)什么希望的地方改造成一個(gè)經(jīng)濟(jì)中心。他們致力于打造一個(gè)“20分鐘社區(qū)”項(xiàng)目,,使當(dāng)?shù)鼐用裰恍枰叫幸粫?huì)兒,,就能在離家不遠(yuǎn)的地方找到購(gòu)物、餐飲,、娛樂(lè)和工作的地方,。一位開(kāi)發(fā)商計(jì)劃收購(gòu)100余套廢棄房屋,然后進(jìn)行翻新改造,,沿著一條連接兩個(gè)大學(xué)校園的“園林路”,,建立一個(gè)混合居住的居民區(qū)。一些非營(yíng)利組織也在收購(gòu)臨街的空白店面,,進(jìn)行翻新后提供給當(dāng)?shù)氐男∑髽I(yè)主,,以便給當(dāng)?shù)鼐用駝?chuàng)造他們一直渴求的就業(yè)機(jī)會(huì)。 梅琳達(dá)·克萊蒙斯帶我們向北走了幾個(gè)街區(qū),,來(lái)到拐角處的一座大型建筑,。這里曾是一家B. Siegel百貨商店。即便是在有“時(shí)尚大道”之稱(chēng)的利沃諾斯大街上,,這間百貨商店也一度稱(chēng)得上地標(biāo)性建筑,。不過(guò)B. Siegel百貨商店早在20世紀(jì)70年代就關(guān)門(mén)了。最近租下這個(gè)地方的是一間一元店,,老板2005年跑路后,,這個(gè)地方已經(jīng)空置了十多年??巳R蒙斯負(fù)責(zé)的一個(gè)項(xiàng)目致力于將這個(gè)地方改造成一個(gè)“迷你社區(qū)”——上面是朝陽(yáng)的兩室一廳,,一棟10戶(hù),下面是一排臨街的餐廳和商店,??巳R蒙斯的童年就是在這里度過(guò)的。她在樓上用手勢(shì)指點(diǎn)江山,,暗示著這里昔日的繁華和如今的潛力:這里是餐廳,、這里是假發(fā)商店和服裝店……她笑著說(shuō):“如果你住在這兒,,這些就都能擁有了?!? 要重建一個(gè)城市,,就要從一個(gè)村子建起。為了底特律的復(fù)蘇,,很多個(gè)人和企業(yè)都投入了大量心力,。不過(guò)在利沃諾斯大街和麥克尼克斯大道的規(guī)劃上,以及在很多其他社區(qū)的建設(shè)上,,有一家企業(yè)的名字經(jīng)常被反復(fù)提及,,這家公司就是摩根大通,。它也是底特律最大的銀行,,它在底特律個(gè)人銀行市場(chǎng)上的占有率達(dá)到了驚人的65%。2014年以來(lái),,摩根大通進(jìn)一步加大了它對(duì)底特律的投入,,并且進(jìn)行了相當(dāng)大膽的試驗(yàn),以幫助底特律的中產(chǎn)階層重新恢復(fù)生機(jī),。 摩根大通的試驗(yàn)叫做“投資底特律”項(xiàng)目,,該項(xiàng)目致力于在最短的時(shí)間內(nèi),同時(shí)振興當(dāng)?shù)胤康禺a(chǎn)市場(chǎng),、幫助當(dāng)?shù)嘏嘤∑髽I(yè),,并且對(duì)居民進(jìn)行就業(yè)培訓(xùn)。摩根大通CEO杰米·戴蒙在紐約總部接受《財(cái)富》采訪(fǎng)時(shí)表示:“如果你沒(méi)有工作,,你就沒(méi)有房子,。如果你沒(méi)有房子,你就沒(méi)法去工作,。另一方面,,如果人們沒(méi)有就業(yè)技能,他們還是買(mǎi)不了房子,。所以必須在這幾個(gè)方面同時(shí)做出進(jìn)展,。” |

That’s why a coalition of Detroiters wants to turn this unlikely tract into an economic hub—part of a “20-?minute neighborhood” where residents could find shopping, restaurants, recreation, and jobs within a short walk from their homes. A developer plans to take over more than 100 abandoned houses and renovate or replace them, creating mixed-income housing along a “greenway” park that will link the college campuses. And nonprofit groups are acquiring some of these blank-faced storefronts, aiming to remake them to host small businesses owned by local entrepreneurs who would hire locally—creating opportunities where they’ve long been absent. A few blocks north, Melinda Clemons shows off a bigger building on a corner lot. This was once a B. Siegel department store, the centerpiece of a stretch of Livernois known as the Avenue of Fashion. B. Siegel closed in the 1970s; the last tenant, a dollar store, fled in 2005. But Clemons is overseeing a project that could turn this vacant hulk into its own mini-neighborhood: a cluster of 10 sunny two-bedroom lofts, sitting atop a parade of street-level restaurants and boutiques. Clemons, who spent her toddler years nearby, gestures down a scrappy block lined with diners, wig shops, and clothing stores that hint at the neighborhood’s prosperous past and present potential. “You could live here,” she says with a grin, “and you’d have all this.” It takes a village to rebuild a city, and the list of people and businesses collaborating on Detroit’s recovery is long. But the planning underway in Livernois/McNichols, and in a growing roster of other neighborhoods, reflects the expertise and financial clout of one corporation in particular: JPMorgan Chase. CEO Jamie Dimon’s financial powerhouse is the largest bank in Detroit, with a titanic 65% market share in consumer banking. Since 2014, the company has been doubling down on that relationship, in a daring experiment to help revitalize Detroit’s middle-class core. The bank’s effort, called Invested in Detroit, is a ?neighborhood-by-neighborhood campaign to revive local real estate, launch small businesses, and train residents for in-demand jobs—all at the same time, as quickly as possible. “If you don’t have jobs, you don’t have housing,” ?Dimon tells Fortune in an interview at JPMorgan Chase’s New York headquarters. “If you don’t have housing, people can’t get to their jobs. If people don’t have skills, people can’t buy homes. You’ve got to make progress on all these fronts.” |

|

要在這些方面取得進(jìn)展,,既離不開(kāi)一個(gè)長(zhǎng)袖善舞的牽頭者,,也需要一群精心挑選的合作伙伴。摩根大通并沒(méi)有直接掏錢(qián)蓋公寓或是給新培訓(xùn)的卡車(chē)司機(jī)發(fā)工資,,不過(guò)正是它的投資才使后續(xù)的這些發(fā)展成為可能,。目前摩根大通已經(jīng)向該項(xiàng)目投資了1.5億美元,,同時(shí)部署了一支輪換團(tuán)隊(duì),幫助底特律的改革派市長(zhǎng)麥克·杜根以及當(dāng)?shù)氐姆怯M織決定對(duì)哪些社區(qū)和產(chǎn)業(yè)進(jìn)行改造升級(jí),。決定相關(guān)投資去向的也是這些利益相關(guān)方和非盈利組織,。比如Capital Impact Partners公司的底特律市場(chǎng)總監(jiān)梅琳達(dá)·克萊蒙斯就是摩根大通團(tuán)隊(duì)的成員之一。她表示:“我們有一些其他大公司沒(méi)有的信息,?!闭沁@些信息,使一些本來(lái)無(wú)法獲得投資的當(dāng)?shù)仄髽I(yè)得到了急需的投資——這些企業(yè)原本得不到投資的原因可能是多方面的,,有經(jīng)驗(yàn)不足這樣的簡(jiǎn)單原因,,也有底特律根深蒂固的種族歧視傾向這種復(fù)雜原因。 這個(gè)項(xiàng)目雖然幫助了窮人,,但它并不是純粹的慈善事業(yè),。摩根大通想培養(yǎng)的企業(yè)不僅要能支付得起工人的工資,同時(shí)還要付得起投資的利息,。摩根大通的企業(yè)責(zé)任總監(jiān)彼得·謝爾指出,,迄今為止,該公司約有55%的投資是由貸款構(gòu)成的,。給一個(gè)女人一條魚(yú),,她一天就吃完了。但如果你教給她如何釣魚(yú),,然后把錢(qián)借給她,,讓她開(kāi)一家炸魚(yú)薯?xiàng)l店,這就超越了做慈善的范疇——這既是善事,,也是一筆好生意,。 在戴蒙看來(lái),投資底特律的商業(yè)價(jià)值也在日益增加,。自從金融危機(jī)爆發(fā)以來(lái),,戴蒙就深信,就業(yè)技能較低的勞動(dòng)者與好的就業(yè)機(jī)會(huì)之間的鴻溝,,其本身已經(jīng)成為拖累全美經(jīng)濟(jì)發(fā)展的一個(gè)重要因素,。如果能夠通過(guò)培育小企業(yè)和對(duì)勞動(dòng)者提供培訓(xùn)來(lái)縮小這種差距,就能建立起一種良性循環(huán),,這意味著更多人能獲得穩(wěn)定的收和,,從而給地區(qū)帶來(lái)更大的繁榮。這樣一來(lái),,更多的企業(yè)家和購(gòu)房者將成為有信用的借貸者,,摩根大通也自然能夠從中獲益。在底特律城區(qū),,摩根大通擁有200億美元的存款,。戴蒙指出:“我們正在不斷獲得市場(chǎng)份額,,摩根大通是每家每戶(hù)都會(huì)選擇的銀行?!蔽覀儾浑y想象,,如果本地經(jīng)濟(jì)得以快速增長(zhǎng),這200億美元的回報(bào)率無(wú)疑是驚人的,。因此,,拿出1.5億美元進(jìn)行城市建設(shè),自然并不是搞慈善這么簡(jiǎn)單,。 |

Making progress involves a deft dance with carefully chosen partners. JPMorgan Chase isn’t directly paying for a thicket of new apartments or a cohort of newly trained truck drivers—but it’s putting up the money to make those efforts possible. The bank has committed $150 million to the project, while deploying a rotating team to help Detroit’s reformist mayor, Mike Duggan, and local nonprofits decide which neighborhoods and industries to saturate. It’s those stakeholders who ultimately decide where the money goes. “We have the intelligence that larger organizations may not have,” says Clemons, the Detroit Market Lead at Capital Impact Partners, one of the bank’s teammates. And that intelligence is steering funds to businesses that wouldn’t otherwise qualify for them—for reasons as simple as inexperience, or as complicated as Detroit’s legacy of racial discrimination. The program may lift up the needy, but it isn’t charity. JPMorgan Chase wants to foster businesses with the skills to pay the bills—with interest. Some 55% of the money it has distributed to date has been made up of loans, says Peter Scher, the bank’s head of corporate responsibility. Give a woman a fish, and she’ll eat for a day. Teach her how to fish, and then lend her money to build a fish-and-chips restaurant, and you’ve gone beyond philanthropy—you’re doing good while doing good business. And the business case for investing in Detroit looks increasingly strong to Dimon. Since the financial crisis, the CEO has become convinced that the gap separating lesser-skilled workers from good job opportunities has itself become a drag on economic growth, nationwide. Do more to close that gap—by fostering small businesses and training workers—and you build a virtuous circle, where more people with stable incomes foster greater prosperity. If that means more entrepreneurs and would-be homebuyers become creditworthy borrowers, JPMorgan Chase wins too. In the Detroit metro area, where the bank has $20 billion in deposits, “We’re gaining share,” Dimon notes. “Chase is the home bank.” Imagine the returns that those $20 billion could earn in a faster-growing local economy, and a $150 million investment in city-building becomes more than simple altruism. |

|

2017年夏天,,摩根大通給了《財(cái)富》一次仔細(xì)觀(guān)察其項(xiàng)目的機(jī)會(huì)——雖然這是一系列小項(xiàng)目,,但它們累積起來(lái)的影響是巨大的。據(jù)謝爾團(tuán)隊(duì)的計(jì)算,,“投資底特律”項(xiàng)目已經(jīng)創(chuàng)造或保住了近1700個(gè)工作崗位,,為大約100家新企業(yè)提供了資金,,為大約15,000名勞動(dòng)者提供了培訓(xùn),。在這樣一個(gè)失業(yè)率超過(guò)10%的城市,這些數(shù)字代表了實(shí)打?qū)嵉倪M(jìn)步,。更重要的是,,它們通過(guò)實(shí)踐證明了摩根大通的理念是可行的。通過(guò)底特律的試驗(yàn),,摩根大通相信,,這種“全面發(fā)力”的底特律模式是可以推廣到全國(guó)的。在接下來(lái)的幾個(gè)月里,,他們就將把底特律模式的一些元素向全美進(jìn)行推廣,。 底特律的衰落程度用一組簡(jiǎn)單的數(shù)字就能看出來(lái)。現(xiàn)在,,底特律大約有67.5萬(wàn)名居民,,而1950年這個(gè)數(shù)字是180萬(wàn)人。早在艾森豪威爾時(shí)代,,底特律的汽車(chē)制造商和國(guó)防承包商們已經(jīng)開(kāi)始積極采用新技術(shù),,以減少對(duì)勞動(dòng)力的依賴(lài)。此后,,很多制造企業(yè)都遷往郊區(qū)或是美國(guó)的其他州,,尋找更大空間建設(shè)更新更高效的工廠(chǎng)。隨著時(shí)間的推移,,幾萬(wàn)名工人也跟著公司離開(kāi)了底特律,。 底特律深入當(dāng)?shù)卣误w系骨髓的種族歧視,,也使那些留下的人深受其害。底特律郊區(qū)至今保持著事實(shí)上的種族隔離,,使黑人員工無(wú)法隨工作而居,。與此同時(shí),當(dāng)?shù)劂y行用“劃紅線(xiàn)”將少數(shù)族裔區(qū)別對(duì)待的做法(即用紅線(xiàn)標(biāo)出少數(shù)族裔聚居區(qū),,以強(qiáng)調(diào)這個(gè)地區(qū)的借貸風(fēng)險(xiǎn)),,也讓黑人家庭難以通過(guò)房產(chǎn)增值來(lái)獲得財(cái)富,同時(shí)也使一些貧困創(chuàng)業(yè)者無(wú)法獲得資本,。再加上所謂的“白人大遷移”,,更使得底特律成為了一個(gè)黑人為主的城市。 上世紀(jì)六七十年代的民權(quán)運(yùn)動(dòng)打破了一些種族藩籬,,但這并沒(méi)有阻止底特律的衰退,。在2007年至2009年,底特律做出了一個(gè)相當(dāng)草率的決定,,不僅將通用汽車(chē)和克萊斯勒逼至破產(chǎn),,也徹底暴露了底特律有多少人欠了次級(jí)房貸。據(jù)研究機(jī)構(gòu)RealtyTrac的數(shù)據(jù)稱(chēng),,在2005年到2014年,,底特律有14萬(wàn)套房子因房主無(wú)力還貸而被銀行收回,本已脆弱不堪的納稅人群體又遭到一次暴擊,,這也進(jìn)一步加速了底特律的破產(chǎn),。 戴蒙是此次災(zāi)難的親歷者之一。他從八十年代起就在這座城市的商界里打拼,。戴蒙曾經(jīng)當(dāng)過(guò)第一銀行(Bank One,,總部在芝加哥)的CEO,當(dāng)時(shí)的第一銀行還是底特律最大的借貸行,。后來(lái)在戴蒙的主導(dǎo)下,,摩根大通于2004年與第一銀行合并,并繼承了其業(yè)務(wù),?!拔覀冋J(rèn)為,底特律早已積重難返,,這場(chǎng)災(zāi)難其實(shí)已經(jīng)醞釀了很多年了,。” |

Last?summer, JPMorgan Chase gave Fortune a closer look at the work it’s supporting—a string of small projects whose cumulative impact is large. Scher’s team calculates that Invested in Detroit has created or preserved nearly 1,700 jobs, financed about 100 new businesses, and reached some 15,000 people through training programs. In a city with unemployment above 10%, those numbers represent real progress. More important, they’re a proof of concept. Thanks to Detroit, the bank is confident that this full-court-press approach is a blueprint that could work across the country—and in the next few months, they’ll be taking components of the Motown model nationwide. You can frame the magnitude of Detroit’s decline with a single statistical juxtaposition: Today, the city has about 675,000 residents, down from 1.8 million in 1950. By the Eisenhower era, the automakers and defense contractors who had fueled Detroit’s boom were already adopting new technology that enabled them to shrink their workforces. Manufacturers moved to suburbs or other states with ample space for new, more efficient factories, and over time, tens of thousands of workers followed the companies out of town. Racial discrimination, baked into local politics and institutions, burdened those who stayed. Many Detroit suburbs maintained a de facto segregation that kept African-American workers from going where the jobs were. Meanwhile, “redlining” by banks—the practice of classifying minority-dominated neighborhoods as too dangerous for lending—kept black families from building wealth through home equity, and starved entrepreneurs of capital, even as “white flight” made Detroit a majority-black city. Civil rights advances in the 1960s and 1970s lowered some barriers, but the erosion continued. The city took a decisive kick in the teeth from the 2007–09 financial crisis, which not only drove General Motors and Chrysler into bankruptcy, but exposed how many Detroit homeowners held subprime mortgages. Some 140,000 Detroit homes were foreclosed on between 2005 and 2014, according to research firm RealtyTrac, shredding the city’s already decimated tax base and helping precipitate its own bankruptcy. Among those witnessing this train wreck was Dimon, who’s been doing business in the city since the 1980s. When Dimon became CEO of Chicago-based Bank One, that institution was Detroit’s biggest lender. JPMorgan Chase inherited that mantle when Dimon engineered its merger with Bank One, in 2004. “We’ve been watching Detroit be an accident waiting to happen for years,” he says. |

|

戴蒙不光趕上了底特律的衰落,,也趕上了它的復(fù)興,。2006年,底特律為了承辦第40屆“超級(jí)碗”杯而在市中心修建了福特體育場(chǎng),,這在一定程度上刺激了市區(qū)的重新開(kāi)發(fā),。2011年,快速貸款公司(Quicken Loans)的董事長(zhǎng)丹·吉爾伯特將公司總部從利沃尼亞市郊搬到了離底特律市政廳只有幾步之遙的馬修斯公園,。自此,,快速貸款公司和吉爾伯特的另一家房地產(chǎn)開(kāi)發(fā)公司——底特律Bedrock公司對(duì)底特律市中心進(jìn)行了不少改造,這兩家公司斥資25億美元,,收購(gòu)和開(kāi)發(fā)了100多處地產(chǎn),。Bedrock公司總裁丹·馬倫曾這樣描述過(guò)公司的哲學(xué):“只要在一個(gè)地區(qū)建立足夠的密度,直到它向四周爆炸輻射,,然后這密度本身就會(huì)帶來(lái)銷(xiāo)路,。”還有一些《財(cái)富》500強(qiáng)公司,,比如汽車(chē)座椅生產(chǎn)商Adient和微軟等等,,也被這里的人流吸引,在底特律市中心開(kāi)設(shè)了辦事處,,隨之而來(lái)的是數(shù)千名知識(shí)工人,。 如果你現(xiàn)在到底特律市中心轉(zhuǎn)轉(zhuǎn),或是坐上快速貸款公司投資建設(shè)的有軌電車(chē)“Q Line”沿著伍德沃德大道去市中心,,一路上你會(huì)看見(jiàn)不少都市白領(lǐng)喜歡的高檔住宅,、品牌專(zhuān)賣(mài)店和休閑娛樂(lè)場(chǎng)所,。John Varvatos和Warby Parker這種時(shí)尚潮牌應(yīng)有盡有,。下了公寓樓,走幾步便是一片老式的棒球場(chǎng),。當(dāng)然,,這里也少不了能喝雞尾酒的高檔餐廳。 復(fù)蘇中的底特律雖然忙忙碌碌,、燈紅酒綠,,但這種復(fù)蘇卻是不完整的。在一個(gè)只有13%的適齡工作人口擁有學(xué)士學(xué)位的城市,,金融和科技行業(yè)工作的涌入對(duì)經(jīng)濟(jì)的推動(dòng)畢竟是有限的,。市長(zhǎng)杜根表示,他不想讓城市出現(xiàn)嚴(yán)重的貧富分化,。他對(duì)《財(cái)富》表示:“我曾仔細(xì)研究過(guò)華盛頓的情況,。另外我的女兒生活在紐約的布魯克林,我也研究過(guò)那里的情況,。我們采取了一定的戰(zhàn)略以避免那種局面發(fā)生,?!辈贿^(guò)你怎樣才能把市中心的繁榮延伸到藍(lán)領(lǐng)和粉領(lǐng)階層呢?底特律的復(fù)蘇怎樣才能不走貧富分化的老路,? 就此,,杜根和摩根大通有一些想法。 |

But Dimon also had a front-row seat for a revival. ?Detroit built Ford Field, a downtown stadium, to host Super Bowl XL in 2006. That helped spark some downtown redevelopment, and the movement gained momentum in 2011, when Quicken Loans Chairman Dan Gilbert moved his headquarters from suburban Livonia to Campus Martius Park, steps from city hall. Since then, Quicken and Gilbert’s development company, Bedrock Detroit, have reshaped downtown, spending some $2.5 billion to acquire and develop more than 100 properties. Dan Mullen, president of Bedrock, describes its philosophy as, “Create enough density in one area until it busts at the seams, and then that density sells itself.” Other Fortune 500 companies—from car-seat maker Adient to Microsoft—have been drawn by the critical mass, establishing offices downtown, and several thousand knowledge workers have moved there too. Visit the central city now, or take the Quicken-funded “Q Line” up Woodward Avenue to Midtown, and you’ll see the kinds of homes, brands, and amenities that white-collar hipsters love. John Varvatos? Warby Parker? Got ’em. An old-fashioned ballpark you can walk to from your loft? Check. Restaurants where the cocktails come with a single, huge ice cube? Roger that. This vision of recovery is buzzy, fun—and incomplete. In a city where only 13% of working-age residents have a bachelor’s degree, the benefits of an influx of finance and tech jobs only stretch so far. Mayor Duggan is adamant that he doesn’t want a stratified city. “I’ve studied closely what happened in Washington, D.C.,” he tells Fortune. “My daughter lives in Brooklyn. I’ve studied what happened there. We are adopting strategies so that doesn’t happen.” But how could you spread downtown’s recovery through the city’s sprawl of blue- and pink-collar neighborhoods? How could you keep Detroit’s boom from replicating America’s economic divide? Duggan had some ideas—and so did JPMorgan Chase. |

|

底特律的復(fù)蘇與摩根大通的捐贈(zèng)理念的轉(zhuǎn)變幾乎是同時(shí)發(fā)生的,。在城市發(fā)展上,摩根大通一向是慷慨解囊的,。光是2016年,,它就向非盈利組織捐贈(zèng)了2.5億美元。不過(guò)在經(jīng)濟(jì)危機(jī)后,,摩根大通的管理層開(kāi)始思考如何讓這筆資金變得更有意義,。在彼得·謝爾的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)下,摩根大通重新制定了自己對(duì)抗底特律經(jīng)濟(jì)衰退問(wèn)題的戰(zhàn)略,,將重點(diǎn)放在了發(fā)展小企業(yè),、工作技能培訓(xùn)、社區(qū)開(kāi)發(fā)和金融咨詢(xún)上,。2012年,,摩根大通約40%的企業(yè)捐款流向了這“四駕馬車(chē)”,現(xiàn)在這一比重已經(jīng)提高到了95%,。這一戰(zhàn)略恰恰也利用了銀行的強(qiáng)項(xiàng)——把資本借給別人,,然后建議他們?nèi)绾瓮顿Y這筆錢(qián)。 在2013年底的時(shí)候,,這種模式對(duì)于摩根大通還很陌生,。不過(guò)戴蒙和謝爾認(rèn)為底特律是一個(gè)理想的實(shí)驗(yàn)室。當(dāng)時(shí)的市長(zhǎng)杜根作為一匹黑馬剛剛勝選,,作為一個(gè)精力充沛,、風(fēng)風(fēng)火火的民主黨籍市長(zhǎng),他與共和黨籍的密歇根州州長(zhǎng)里克·斯奈德的關(guān)系反倒是相當(dāng)和諧,。戴蒙回憶道:“他們整天說(shuō)的都是:‘我們需要工作,,我們需要房子,我們需要把這些燈點(diǎn)亮’,,而不是糾結(jié)于意識(shí)形態(tài)的紛爭(zhēng),。”底特律退出破產(chǎn)程序后,,城市得以擺脫了一些債務(wù)負(fù)擔(dān),,能夠?qū)⒏喽愂栈ㄔ诟纳瞥鞘协h(huán)境上。最重要的是,謝爾和杜根發(fā)現(xiàn),,他們?cè)谏鐓^(qū)建設(shè)和促進(jìn)居民自力更生上有許多觀(guān)點(diǎn)是一致的,。到2014年7月,摩根大通已經(jīng)為“投資底特律”項(xiàng)目投入了1億美元,。 有人可能要問(wèn),,摩根大通2016年的營(yíng)收入達(dá)到了1060億美金,這樣一家大銀行,,為什么只拿出這點(diǎn)錢(qián)援助底特律,?如果它有心,為什么不瘋狂地向底特律的企業(yè)家放貸呢,?簡(jiǎn)單說(shuō)來(lái),,心急吃不了熱豆腐,摩根大通也沒(méi)辦法,,因?yàn)檫@些借款人并不一定是銀行眼中“有貸款資格”的人,。 這也反映了底特律陷入持續(xù)衰落的惡性循環(huán)背后的經(jīng)濟(jì)原理。按照法律規(guī)定,,大多數(shù)銀行在貸款時(shí)都要保持一定的“貸款價(jià)值比”,,也就是貸款額與擔(dān)保物價(jià)值的比例,這個(gè)比例必須低于一定的門(mén)檻——通常是80%,。然而底特律大部分地區(qū)的房?jī)r(jià)跌得極慘,,大多數(shù)房地產(chǎn)項(xiàng)目很容易就會(huì)打破這個(gè)上限。也就是說(shuō),,建筑這些房產(chǎn)所花的成本,,可能要比它建好后的售價(jià)還要高。出于同樣的原因,,當(dāng)?shù)仄髽I(yè)家們也很難湊夠一筆抵押品來(lái)申請(qǐng)貸款,。不過(guò)快速貸款公司(Quicken Loans)并不存在這樣的困難,它早期在底特律市中心的幾筆投資都是自己掏的腰包,。對(duì)于底特律的其他大公司來(lái)說(shuō),,要找一家愿意提供貸款的銀行也非難事。但小企業(yè)和本地的房地產(chǎn)開(kāi)發(fā)公司就沒(méi)有這么幸運(yùn)了,。 |

Detroit’s reemergence coincided with a philosophical shift at the bank. It’s already a formidable donor: In 2016, it gave $250 million to nonprofits. But after the financial crisis, its leadership began considering how to make that money count for more. Under Peter Scher, it retooled its giving to tackle economic insecurity itself—focusing on small-business expansion, job-skills training, neighborhood development, and financial counseling. In 2012, about 40% of JPMorgan Chase’s corporate giving was devoted to those four pillars, Scher says; today, it’s 95%. It’s an approach that leverages what banks already do well—lending people capital, and giving them advice about how to deploy it. In late 2013, this model was new for the bank. But Dimon and Scher saw in Detroit an ideal laboratory for it. There was rare harmony between Duggan—an energetic, bulldozer Democrat who had just won an election, amazingly, as a write-in candidate—and Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican. “All they spoke about was, ‘We need jobs, we need housing, we need to turn the lights on,’?” Dimon recalls. “Not the ideological yelling and screaming.” Detroit’s exit from bankruptcy enabled the city to shed some of its elephantine debt obligations and dedicate more tax revenue to improving the city. Most important: Scher and Duggan found they shared many beliefs about neighborhood-building and economic empowerment. By July 2014, JPMorgan Chase had put $100 million on the table for Invested in Detroit. It’s fair to ask why JPMorgan Chase, a bank that generated $106 billion in revenue in 2016, wasn’t already lending like crazy to Detroit’s entrepreneurs. The answer was that it essentially couldn’t—because those borrowers weren’t “bankable.” That fact reflects the self-perpetuating math of Detroit’s decline. Most banks are required by law to keep “l(fā)oan-to-value ratios”—the ratio of the loan amount to the estimated worth of the project it funds—below a certain threshold, typically 80%. But property values in most of Detroit have sunk so far that most real-estate projects easily break that ceiling; by definition, they would cost more to build than they would be worth once completed. For similar reasons, entrepreneurs can seldom scrape together collateral for a loan. Quicken Loans didn’t face this problem—its early downtown investments were self-financed. And Detroit’s big corporations can almost always find lenders. But small businesses and local developers are often stymied. |

|

不過(guò)摩根大通找到了繞過(guò)這些障礙的方法。美國(guó)所謂的“社區(qū)發(fā)展金融機(jī)構(gòu)”(簡(jiǎn)稱(chēng)CDFI)專(zhuān)門(mén)負(fù)責(zé)為低收入社區(qū)提供貸款,。CDFI通常是非營(yíng)利性組織,,財(cái)政部也不硬性要求他們遵守一些針對(duì)營(yíng)利性銀行的規(guī)則。CDFI可以承擔(dān)更大風(fēng)險(xiǎn),,也能接受更高的貸款價(jià)值比,,而且貸款條件也相對(duì)寬松,。他們還可以貸款給那些信用評(píng)分不高或是缺乏信用記錄的企業(yè)家,而其他銀行對(duì)于這種企業(yè)家肯定是敬而遠(yuǎn)之的,。摩根大通由全球慈善副總裁托莎·塔布倫牽頭,,選擇了三家CDFI合作伙伴從事這項(xiàng)工作。塔布倫是個(gè)土生土長(zhǎng)的底特律人,,而且有著豐富的CDFI領(lǐng)域的經(jīng)驗(yàn),。目前摩根大通已向這三家CDFI提供了5000萬(wàn)美元的貸款和撥款,并任由他們將這些資金分配到正確的地方,。 “有色企業(yè)家基金”(Entrepreneurs of Color Fund)就是致力于這項(xiàng)工作的組織之一,,它是由底特律發(fā)展基金會(huì)(DDF)創(chuàng)辦的。自2015年創(chuàng)立以來(lái),,該基金會(huì)已經(jīng)向47名借款人發(fā)放了420萬(wàn)美元貸款,。DDF理事長(zhǎng)雷伊·沃特斯表示:“他們之中的95%通過(guò)正常渠道是拿不到銀行貸款的?!蔽痔厮箷?huì)幫助他們制訂商業(yè)計(jì)劃,,然后為他們提供會(huì)計(jì)和營(yíng)銷(xiāo)方面的培訓(xùn),好將他們的業(yè)務(wù)做大做久,。在這些人中,,生意做得最大的一個(gè)年收入可達(dá)80萬(wàn)美元——雖然這種小生意在銀行看來(lái)不值一提,但卻足以對(duì)一個(gè)社區(qū)產(chǎn)生重大影響了,。沃特斯表示:“你開(kāi)了一家小小的墨西哥餐廳,,雇了十個(gè)人每天走路來(lái)上班。你怎可能說(shuō)它不好呢,?” 沃特斯指出,,CDFI貸款的利率通常為7%或8%,而銀行貸款的利率一般是4%到5%,。這既反映了CDFI提供的額外支持的成本,,也充分說(shuō)明了CDFI貸款面臨的高風(fēng)險(xiǎn)——DDF的違約率略高于4%,而普通商業(yè)貸款的違約率大約是1.35%,,也就是說(shuō)前者的違約風(fēng)險(xiǎn)是后者的三倍,。不過(guò)一旦CDFI的受益人做得成功了,他們?cè)阢y行眼里也就變成了“有資格”的貸款者,,他們的違約風(fēng)險(xiǎn)也就小得多,。 艾德麗安和A.K.·班尼特母子在城市西北角的一座老樓里開(kāi)了一家小公司,主要經(jīng)營(yíng)水電工服務(wù),,取名叫Benkari機(jī)械公司,。去年,Benkari公司抓住了一個(gè)大機(jī)會(huì),可以承包小凱撒競(jìng)技場(chǎng)——也就是底特律的新冰球場(chǎng)館的部分水電工程,。不過(guò)這個(gè)工期要持續(xù)60到90天才能回款,,他們這家母子店一時(shí)沒(méi)有足夠的現(xiàn)金給工人發(fā)薪水。以這家小公司的條件,,也不可能從銀行申請(qǐng)到貸款,。 有色企業(yè)家基金為Benkari公司提供了一筆30萬(wàn)美元的貸款,最終使Benkari公司贏得了競(jìng)標(biāo),。小凱撒競(jìng)技場(chǎng)的工程將使Benkari公司在2017年成功賺到第一個(gè)100萬(wàn)美金,。在證明了自己的實(shí)力后,又有很多大項(xiàng)目自動(dòng)找上了門(mén),。如果這一發(fā)展勢(shì)頭持續(xù)下去,,這家小公司會(huì)不會(huì)在10名員工的基礎(chǔ)上再招幾個(gè)人?艾德麗安答道:“這不是‘如果’的問(wèn)題,,而是‘什么時(shí)候’的問(wèn)題,。” “今天是收垃圾的日子,。你能在收垃圾日學(xué)到很多東西,。”戴夫·布拉斯基維茨開(kāi)著一輛大型SUV,,沿著一條居民區(qū)的狹窄小路行駛,,這里是麥克尼克斯大道以北,離那里的零售區(qū)域并不遠(yuǎn),。對(duì)于沒(méi)有經(jīng)過(guò)訓(xùn)練的人,,這排平房的健康狀況是很難評(píng)估的。有些房子極為老舊,,有的已經(jīng)破壞不堪,,有的干脆已經(jīng)被廢棄了。但大多數(shù)房子門(mén)前都矗立著一個(gè)大大的塑料垃圾桶,,等待著收垃圾的卡車(chē)將它們清走,。而這就是社區(qū)力量的一個(gè)象征。 布拉斯基維茨是一家名叫InvestDetroit的CDFI的理事長(zhǎng),。InvestDetroit主要關(guān)注房地產(chǎn)和小企業(yè)的發(fā)展,,它也是摩根大通選擇的另一個(gè)CDFI伙伴。在市中心和城區(qū)的復(fù)蘇中,,他堅(jiān)信“密度就是一切”的信條,。他說(shuō),即使是在那些看起來(lái)很破敗的社區(qū)里,,也有很多被壓抑的居民需求,足以使一些小企業(yè)蓬勃發(fā)展。 |

JPMorgan Chase spotted a way around the obstacle. Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) specialize in lending to lower-income communities. They’re usually nonprofits, and the Treasury Department exempts them from some rules that govern for-profit banks. CDFIs can take greater risks, accepting higher loan-to-value ratios and extending relatively lenient payment terms. They can also lend to entrepreneurs whose credit scores or lack of a track record would drive banks away. Guided by vice president of global philanthropy Tosha Tabron, a Detroit native with extensive CDFI experience, JPMorgan Chase chose three as partners. It has since extended more than $50 million to them through loans and grants—and given them a free hand to get it to the right places. One such group is the Entrepreneurs of Color Fund, an initiative operated by the Detroit Development Fund (DDF). The fund has loaned $4.2 million since its inception in 2015, to 47 borrowers, “95% of whom could not get a bank loan,” according to DDF president Ray Waters. Waters and his partner groups help them develop business plans and train them in accounting and marketing, so they’re able to sustain what they build. The biggest have about $800,000 a year in revenue—too small to get attention from banks, but big enough to make a neighborhood impact. “You open a little taqueria, you’ve got 10 employees who are all walking to work” because they live nearby, Waters says. “How can you feel bad about that?” CDFI loans typically carry interest rates of 7% or 8%, Waters says, compared with 4% to 5% for a bank business loan. That reflects both the costs of the additional support the lenders offer, and the greater risk: Default rates at DDF, at a little over 4%, are almost three times as high as the 1.35% average for commercial loans. But the nonprofits’ most successful protégés can grow large enough to be “bankable”—and look like much less risky bets. Adrienne and A.K. Bennett, mother and son, run their plumbing and HVAC contracting firm, Benkari Mechanical, out of a cluttered cinder-block building on the city’s northwest side. Last year, Benkari got a big opportunity: The chance to work on Little Caesars Arena, Detroit’s new hockey venue. But it didn’t have the cash to cover payroll for the 60-to-90 days between when the job started and when the checks arrived—and it wasn’t well established enough to borrow it from a bank. The Entrepreneurs of Color Fund extended a $300,000 loan to cover the costs—enabling Benkari to win the bid. The arena work has put Benkari on track for its first million-dollar year in 2017. And having proved it can skate with the pros, Benkari is a candidate for some lucrative contracts at federal buildings downtown. If the momentum continues, will the Bennetts expand their 10-person staff? “If?” retorts Adrienne. “It’s not ‘if.’ It’s ‘when.’?” "Oh, nice, it’s trash day," says Dave Blaszkiewicz. “You learn a lot on trash day.” He’s piloting an enormous SUV down a narrow residential street, just north of the McNichols retail strip. To the untrained eye, the health of this block of brick bungalows might be hard to gauge. Some homes are pristine, some are run-down, some are abandoned “broken teeth.” But most have big plastic trash bins waiting for pickup in their driveways—and that’s a sign of neighborhood strength. Blaszkiewicz is the president and CEO of InvestDetroit, a CDFI with a focus on real estate and small-business development; it’s another JPMorgan Chase partner. Working on the downtown and midtown revivals converted him to the “density is everything” mantra. Even in neighborhoods that look blighted, he says, there’s often enough pent-up demand among residents to kindle a small-business boom. |

|

摩根大通已經(jīng)向底特律的幾家非營(yíng)利性基金投資了3000萬(wàn)美元,,以尋找那些有可能“冒尖”的社區(qū),從而推動(dòng)小企業(yè)的增長(zhǎng)?,F(xiàn)在的問(wèn)題是,,在底特律的大多數(shù)地區(qū),老百姓的錢(qián)袋子還不夠深,,因此無(wú)論多少投資都無(wú)法吸引出走的企業(yè)回流——至少現(xiàn)在是這樣,。正如杜根所說(shuō)的:“我不能告訴那些開(kāi)鞋店、雜貨店和咖啡店的應(yīng)該去哪里開(kāi)店,?!? 底特律的這幾家CDFI最迫切的愿望是建立一個(gè)數(shù)據(jù)庫(kù),從而幫助他們預(yù)測(cè)哪些社區(qū)最能從他們的推動(dòng)中獲益,。為了建立這樣的數(shù)據(jù)庫(kù),,摩根大通從全國(guó)各地請(qǐng)來(lái)了四名員工,以展示他們強(qiáng)大的數(shù)據(jù)分析能力,。研究小組收集了任何能夠量化的關(guān)于社區(qū)健康的數(shù)據(jù),,包括附近的餐館、交通設(shè)施和當(dāng)?shù)貙W(xué)校的質(zhì)量等等,。他們還分析了信用卡交易數(shù)據(jù),,研究了當(dāng)?shù)厝说南M(fèi)模式。另外他們還參加了幾十次社區(qū)會(huì)議,,以了解當(dāng)?shù)鼐用褡钕胍裁礃拥钠髽I(yè),。摩根大通企業(yè)與投資銀行部全球研究總監(jiān)喬伊斯·張表示:“這就像在投行一樣,你會(huì)把各種機(jī)會(huì)按‘綠色’,、‘琥珀色’和‘紅色’進(jìn)行評(píng)級(jí),。” 最終,,他們成功建立了一個(gè)可以有效輔助投資決策的靈活的數(shù)據(jù)庫(kù),。布拉斯基維茨表示:“他們一個(gè)月就做了其他人半年才能做到的事?!薄巴顿Y底特律”項(xiàng)目瞄準(zhǔn)的前三個(gè)“微商區(qū)”的各種資產(chǎn)類(lèi)型都能在數(shù)據(jù)庫(kù)中顯示出來(lái),,包括前文提到的利沃諾斯大道和麥克尼克斯大道。比如相對(duì)比較荒涼的麥克尼克斯路,,在步行可達(dá)的范圍內(nèi),,就有兩塊比較繁榮的商區(qū)、舍伍德林區(qū)和大學(xué)區(qū),,居民平均年收入達(dá)到8萬(wàn)美元左右,。向北不遠(yuǎn)就是時(shí)尚大道,。這里的鞋店和服裝店都有些年頭了,有時(shí)會(huì)給人一種時(shí)空穿梭的錯(cuò)亂感,,很多牌子都是汽車(chē)城時(shí)代的遺產(chǎn),,不過(guò)他們的生意還算興隆,他們的勢(shì)頭也能帶動(dòng)附近街區(qū)的增長(zhǎng),。 摩根大通的塔布倫表示:“我沒(méi)有見(jiàn)過(guò)這個(gè)城市的全盛時(shí)期,。”塔布倫是在大學(xué)區(qū)長(zhǎng)大的,。不過(guò)她表示,,這里和一些社區(qū)依然保持著旺盛的商業(yè)脈搏?!艾F(xiàn)在我們已經(jīng)有了擴(kuò)展它的模板,。” 這種“模板”的建筑特色,,便是“商住混用”,,即上層是住宅、下層是商鋪的地產(chǎn)項(xiàng)目,。這些項(xiàng)目可以成為區(qū)域經(jīng)濟(jì)的“瑞士軍刀”,,促進(jìn)多種商業(yè)的發(fā)展。另外它們可以吸引許多富裕的租戶(hù),,同時(shí)房?jī)r(jià)也能讓普通居民負(fù)擔(dān)得起,。按照現(xiàn)在的計(jì)劃,“投資底特律”項(xiàng)目瞄準(zhǔn)的每個(gè)“微街區(qū)”至少要有兩個(gè)這樣的“商住混用”小區(qū),。 克萊蒙斯所在的CDFI就是專(zhuān)門(mén)從事這種項(xiàng)目的,。利沃諾斯大道上的B. Siegel項(xiàng)目就是一個(gè)這樣的項(xiàng)目。在一個(gè)炎熱的下午,,克萊蒙斯和他的同事又帶我去了另一個(gè)項(xiàng)目“the Coe at West Village”的工地,。該項(xiàng)目預(yù)計(jì)于去年11月開(kāi)盤(pán)。旁邊的街區(qū)有兩家深受當(dāng)?shù)厝讼矏?ài)的老店,,一家是理發(fā)店Heavyweight Cuts,,一家是烘培店Sister Pie。項(xiàng)目開(kāi)發(fā)商克里夫·布朗帶著我們四處參觀(guān),。他的體型相當(dāng)健碩,,安全帽在他頭頂小得有些滑稽。這是他作為開(kāi)發(fā)商接手的第一個(gè)項(xiàng)目,。若不是CDFI的資助,,他幾乎肯定申請(qǐng)不到傳統(tǒng)貸款。該項(xiàng)目耗資約400萬(wàn)美元,,其中差不多有一半的資金來(lái)自摩根大通,。 |

JPMorgan Chase has invested some $30 million in Detroit-based funds that fuel that kind of growth by spotting neighborhoods that could be about to “tip.” The problem: In much of Detroit, the pockets of strength aren’t big enough, and no amount of investment can lure business back, at least right now. As Duggan puts it, “I can’t tell the shoe store or grocery store or the coffee shop where to go.” High on the wish list for Detroit’s CDFIs was a database that could help them predict which neighborhoods could best take advantage of a push. To build one, JPMorgan Chase brought in four employees from around the country to flex their data-science muscles. The team gathered anything they could quantify about neighborhood health—number of sit-down restaurants, transit availability, quality of local schools. They looked at credit card transaction data, gleaning insights about spending patterns. And they went to dozens of neighborhood meetings to learn what kinds of businesses residents wanted. “It’s like in investment banking, where you rank an opportunity ‘green,’ ‘a(chǎn)mber,’ or ‘red,’?” says Joyce Chang, the bank’s New York–based global head of research for corporate and investment banking, who mentored the team. The result was a flexible, user-friendly database that could shape decision-making. “They did in a month what would have taken someone else six,” says Blaszkiewicz. The kinds of assets that the database is designed to detect are on display in the first three eight-to-15-block “micro?districts” targeted by Invested in Detroit—including Livernois/McNichols. Within walking distance of the desolate part of McNichols Road, for example, are two prosperous tracts, Sherwood Forest and the University District, where household incomes average around $80,000. A short distance north is the Avenue of Fashion. The shoe stores and dress shops on those blocks have a time-capsule air about them—many of the signs are of Motown vintage—but they do brisk business, and the momentum they generate could help nearby blocks grow too. “I didn’t witness the heyday of the city,” says JPMorgan Chase’s Tabron, who grew up in the University District. But neighborhoods like hers have sustained a commercial pulse, she says, and “now we’ve got this template to expand it.” If that template has an architectural signature, it’s the “mixed-use” building—boxy new construction that combines residential units with ground-floor retail. These projects can be a Swiss Army knife for development: They can host multiple businesses; they’re well suited to loft spaces that attract affluent renters; and they can accommodate affordable housing. Under current plans, each of the microdistricts targeted by Invested in Detroit’s partners will have at least two new mixed-use hubs. Capital Impact, Clemons’s CDFI, specializes in these projects. The B. Siegel project on Livernois is one, and on a hot afternoon, Clemons and a colleague take me to another. We pull into a site due to open in November as “the Coe at West Village.” It sits about a block from two beloved “anchors” of the West Village neighborhood: a barbershop, Heavyweight Cuts, and a bakery, Sister Pie. Cliff Brown, a broad-shouldered man on whom a construction helmet looks comically small, shows us around. It’s one of his first projects as a developer, and he almost certainly couldn’t have financed it with a traditional loan; just under half of the $4 million cost is coming from funds backed by JPMorgan Chase. |

|

布朗表示,,該項(xiàng)目目前還處于毛墻毛地的階段,,不過(guò)在12個(gè)單元已經(jīng)有7個(gè)租出去了,。另外有一家動(dòng)感單車(chē)健身房的老板也瞄準(zhǔn)了這里的商業(yè)空間,。隨后,布朗為我們展示了一套平價(jià)住房的空間布局,,這套房子的月租金是944美元,。這套房子有巨大的落地窗,還有一個(gè)陽(yáng)臺(tái),,和旁邊高檔住宅樓里的房子沒(méi)什么區(qū)別,。布朗說(shuō):“我小時(shí)候住在一個(gè)很破舊的小區(qū)。等我進(jìn)入建筑行業(yè)以后,,我經(jīng)常想:‘如果我能為我的朋友們建一套房子,,它會(huì)是什么樣的?’這就是我的理念的具體化,?!? 當(dāng)然,對(duì)于很多底特律人來(lái)說(shuō),,要拿出944美元的月租也是很吃力的,。要知道,底特律的中位家庭收入只有不到26000美元,,還不到全國(guó)平均水平的一半,。確保更多底特律人有工作,從而掏得起更高的租金,,則是擺在昌西·列儂面前的難題,。列儂是摩根大通的勞動(dòng)力計(jì)劃總監(jiān),他的部門(mén)主要負(fù)責(zé)將沒(méi)有大學(xué)學(xué)歷的工人匹配到中等薪水的“中等技能”工作上——這些工作經(jīng)常由于人才短缺而招不到人,。列儂表示:“很多家庭都有‘不上大學(xué)就掙不到錢(qián)’的心態(tài),。這種心態(tài)不能說(shuō)完全是錯(cuò)的,但它不能幫助人們做出最好的選擇,?!? 列儂的團(tuán)隊(duì)針對(duì)底特律的就業(yè)市場(chǎng)進(jìn)行了一項(xiàng)調(diào)查,以確定就業(yè)市場(chǎng)上供給與需求的差距,。為了彌補(bǔ)這種差距,,迄今為止,摩根大通已經(jīng)投入了1500萬(wàn)美元,。列儂的部門(mén)幫助20所公立高中設(shè)計(jì)了職業(yè)主題課程,,并且組織了部分企業(yè)以學(xué)徒或?qū)嵙?xí)的形式聘用學(xué)生從事水管工或醫(yī)院護(hù)工等工作,。 摩根大通還資助了像“Focus: HOPE”這樣的非營(yíng)利組織。Focus: HOPE是一個(gè)職業(yè)性的學(xué)習(xí)中心,,學(xué)生可以在這里通過(guò)“整合先進(jìn)制造”課程,,學(xué)習(xí)如何操作工廠(chǎng)中常見(jiàn)的機(jī)器人工具。去年5月,,杜根和謝爾在新聞發(fā)布會(huì)上宣布,,摩根大通將向“投資底特律”項(xiàng)目追加投資5000萬(wàn)美元,使項(xiàng)目總投資達(dá)到1.5億美元,。Focus: HOPE就是他們選擇的投資渠道之一,。學(xué)員們有時(shí)要豎起耳朵才能聽(tīng)見(jiàn)彼此的說(shuō)話(huà)聲,因?yàn)檎n堂里到處都是金屬撞擊的叮叮當(dāng)當(dāng)聲,。 重建底特律是一項(xiàng)長(zhǎng)期而艱巨的工程,。光是前三個(gè)“微商區(qū)”就要到2021年才能全部建成。底特律希望到2026年前建成10個(gè)這樣的“微商區(qū)”,。要想培養(yǎng)足夠的工作崗位以保持這些微商區(qū)的發(fā)展勢(shì)頭,,也需要同樣長(zhǎng)的時(shí)間。我們盡可以想象屆時(shí)到利沃諾斯大道和麥克尼可斯大道購(gòu)物的情形,,但短期內(nèi),,這里還是不值得專(zhuān)程來(lái)一趟。 雖然需要漫長(zhǎng)的等待,,但摩根大通的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)層卻并不灰心,。謝爾表示:“一個(gè)政治家在臺(tái)上只有四年時(shí)間,但一個(gè)銀行家卻有20年可以施展抱負(fù),?!辈贿^(guò)到目前為止,摩根大通的投資已經(jīng)初步見(jiàn)到了成效,。它向CDFI提供的貸款已經(jīng)有了回報(bào),,迄今償還額已達(dá)890萬(wàn)美元,這筆錢(qián)又重錢(qián)投入到了“投資底特律”項(xiàng)目,。謝爾指出,,該項(xiàng)目迄今還沒(méi)出現(xiàn)任何一例違約。 該項(xiàng)目也為摩根大通培養(yǎng)和保留了很多頂尖人才,。迄今已有80多名員工在摩根大通的“底特律服務(wù)團(tuán)”進(jìn)行了輪崗和培訓(xùn),。而且“底特律服務(wù)團(tuán)”的競(jìng)爭(zhēng)還是相當(dāng)激烈的,經(jīng)常出現(xiàn)好幾名員工同時(shí)競(jìng)爭(zhēng)一個(gè)機(jī)會(huì)的情況,?!八苋菀鬃尪鄽q的年輕人產(chǎn)生共鳴?!痹?jīng)做過(guò)社區(qū)記分卡工作的喬伊斯·張說(shuō),。 最重要的是,,“投資底特律”項(xiàng)目經(jīng)過(guò)三年的實(shí)踐,戴蒙和摩根大通的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)團(tuán)隊(duì)相信,,他們已經(jīng)找到了讓美國(guó)各大城市重新煥發(fā)生心機(jī)的良方,。到去年年底,他們就將把“定點(diǎn)扶貧”的底特律模式推廣到密歇根州以外的地方,。 去年8月,,摩根大通宣布,將在芝加哥南區(qū)投資建設(shè)BSD職業(yè)中心,,它就是以底特律的Focus: HOPE為藍(lán)本建立的,。9月晚些時(shí)候,摩根大通還將在其他三個(gè)城市啟動(dòng)社區(qū)支持項(xiàng)目,,項(xiàng)目所用的撥款均來(lái)自摩根大通的“社區(qū)支持基金”(Pro Neighborhoods Fund)。大約就在同一時(shí)間,,摩根大通還將在舊金山灣區(qū)設(shè)立一個(gè)新的“有色企業(yè)家基金”,。另外,也是在去年秋天,,摩根大通將對(duì)另一個(gè)美國(guó)大城市啟動(dòng)全套的“底特律模式”——即對(duì)小企業(yè)發(fā)展,、住宅開(kāi)發(fā)和就業(yè)培訓(xùn)進(jìn)行大量投資,從而重建當(dāng)?shù)氐闹挟a(chǎn)階層,。 戴蒙表示:“我們不能在每個(gè)地方都采用底特律模式,,但我們每年可以底特律模式推廣到三四個(gè)地方,然后在另外十個(gè)地方采用‘簡(jiǎn)化版的底特律模式’,?!敝劣谠鯓油茝V,以及在哪里推廣,,“我們已經(jīng)有名單了,。”他說(shuō),。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng)) 譯者:Min |

Construction is still in the drywall stage, but seven of the 12 units are leased, Brown says, and the owner of a spinning gym is eyeing the retail space. He shows off the shell of an affordable-housing unit that will rent for $944 a month. The studio has huge picture windows and a balcony, just like its bigger neighbors in the complex. “I grew up with kids who lived in beat-up housing projects,” Brown says. “When I got into construction, I thought, ‘What kind of house would I build for our friends?’ This is that idea in action .” Of course, $944 a month is a stretch for many in Detroit. Median household income in the city is under $26,000—less than half the national average. Making sure that more Detroiters have jobs that can keep up with higher rents is a job for Chauncy Lennon. Lennon is JPMorgan Chase’s head of workforce initiatives, and his group’s mandate includes steering workers without college degrees toward “middle skill” jobs that pay middle-class salaries—jobs that often go unfilled because of talent shortages. “A lot of families and educators have a ‘B.A.-or-bust’ mentality,” Lennon says. “That’s not wrong as far as it goes, but its not helping people make the best choices.” In Detroit, Lennon’s team helped spearhead a survey of the job market, to identify the gaps between demand and supply. To date, JPMorgan Chase has invested $15 million in filling those gaps. Lennon’s group is helping design career-themed curriculums at 20 public high schools—and organizing businesses to hire students for apprenticeships and internships in fields like plumbing and hospital work. The bank is also funding nonprofits like Focus: HOPE, a vocational center where students in an “integrated advanced manufacturing” course work with the kind of robotics tools used in today’s factories. When Duggan and Scher hosted a press conference in May to announce that ?JPMorgan Chase was steering another $50 million to Invested in Detroit, bringing the total to $150 million, they chose Focus: HOPE as the venue. Audience members sometimes had to strain to hear them; they were competing with the metal-on-metal clangor from the shop-class floor. Rebuilding Detroit’s neighborhoods is nothing if not a long game. The projects in the first three microdistricts should be finished by 2021; the city hopes to build out 10 neighborhoods by 2026. Cultivating jobs to sustain those neighborhoods will take just as long. Fantasize about a shopping trip to Livernois/McNichols, in other words, but don’t book it any time soon. JPMorgan Chase’s leaders aren’t fazed by the wait. “A politician has a four-year horizon,” Scher says. “A banker can have a 20-year horizon.” But so far, the bank’s bet is paying off. Its loans to CDFIs have already reaped returns, with $8.9 million to date repaid and cycled back into Invested in Detroit projects; Scher says there hasn’t been a single default. The project is also helping the bank retain and develop top talent. JPMorgan Chase has cycled more than 80 employees through its Detroit Service Corps to provide advice and training for a few weeks at time. Those postings are competitive, with multiple candidates applying for each opening. “It’s so much more in touch with what people in their twenties want to do,” says Chang, the executive who worked on the neighborhood scorecard. But most important, three years of progress with Invested in Detroit has convinced Dimon and his leadership team that they’ve assembled the right tool kit for revitalizing American cities. And by the end of the year they’ll have planted the flag beyond Michigan. In August, JPMorgan Chase announced an investment in BSD, a vocational center on Chicago’s South Side modeled after Focus: HOPE. Later in September, the bank will unveil its support for neighborhood-building projects in three more cities, to be financed by grants from its Pro Neighborhoods Fund. Around the same time, the bank will launch a new Entrepreneurs of Color fund in the San Francisco Bay Area. And another major metro area, to be announced this fall, will be the next to get the full Motor City treatment?—a multipronged blitz of funding for small businesses, residential development, and job-skills work that could help rebuild its middle class. “We can’t do Detroit everywhere,” Dimon says. “But we could do Detroit in three or four places a year, and we could do a ‘Detroit lite’ in another 10.” Figuring out how, and where? “It’s on the list,” he says. |